26 November, 2003

A windy day here at camp, with a weather report calling for even

stronger winds and some snow later in the day. Definitely not a

great forecast if you want to photograph and weigh seals, so it was

time to come up with some alternative plans. Since I'd been hoping

to visit one of the other research camps out on the ice, this seemed

like a perfect opportunity. After calling ahead to find out what

time might be best for our visit, we saddled up our snowmobiles and

headed off for the Penguin Ranch.

Now, the Penguin Ranch is not your ordinary ranch. There are no

cowboys and the only livestock they work with is a small group of

Emperor Penguins. The head of ranch operations is Dr. Paul Ponganis,

a research physiologist based out of the Scripps Institute of

Oceanography, who is examining the diving physiology of the Emperor

Penguin. These birds regularly dive to depths of up to 500 meters,

spending 8 to 10 minutes at a time underwater. His group is

measuring the effects of those dives on the oxygen content of the

birds' blood. Another member of the ranch crew, Katsu Sato of

Tokyo's National Institute of Polar Research, is testing new data

recorders that can be attached to the penguins.

Emperor Penguins are difficult to study in the wild. The Penguin

Ranch has developed techniques for studying them 'almost' in the

wild-they have 13 to 14 penguins at any one time living in a corral

at the ranch. This corral has a low fence, and is equipped with 2

dive holes through the ice. Since these are the only holes for many

kilometers, the penguins will dive and return through the same hole,

remaining within the corral between dives. The penguins can be

caught, anesthetized, and equipped with sensors that monitor oxygen

saturation levels in their blood stream and in the air sacs of their

lungs while they are diving under the ice and retrieved from the

penguins after their days dives are completed. In addition, some of

the penguins have been equipped with Katsus's data recorders. These

recorders have a small accelerometer that measures how fast they are

going underwater, as well as sensors that can measure the speed, body

angle, and the depth of the dive. The entire sensor package is less

than 15 cm long and is light enough to be attached to the penguin's

back.

Data collected during the dives has shown that the blood oxygen

concentration in the birds can go from 20% down to 2% at the end of a

diving sequence. This group is working to find out what the aerobic

threshold might be for the penguins and how this might limit the

length or depth of their dives. Katsu's work this season is focusing

on perfecting the sensors. A few years ago he worked with the Weddell

Seal project at Big Razorback, using sensors to determine diving

depths and foraging behavior for some of those seals. Katsu worked

with TEA Kolene Krysl while at Big Razorback-so you can learn more

about his work there by accessing her journals from the archives.

The sensors he is using on the penguins are miniature versions of

those used on the seals. He pointed out one big difference between

the way a seal dives and how a penguin dives-seals glide downward

through the water column and use their flippers to propel themselves

back up, while the penguins stroke on the downward trip and glide to

the surface.

The logistics of creating a penguin corral are interesting. Once a

hole is drilled through ice, it presents an open invitation for

Weddell Seals. To prevent seals from coming up through the ice in

the center of the corral, the researchers have drilled two additional

holes through the ice in unique locations-under their lab and kitchen

huts. Each of these huts has removable hatches in their floors that

can be opened to expose the holes below. While we were talking with

Dr. Ponganis in his lab, Wally the Seal surfaced every few minutes to

exhale loudly and take a gulp of fresh air. Not everyone can say

that they have a seal in their lab! At night the penguin's holes are

'corked' with a large, insulated circle of plywood to prevent them

from escaping and to keep out unwanted seal visitors.

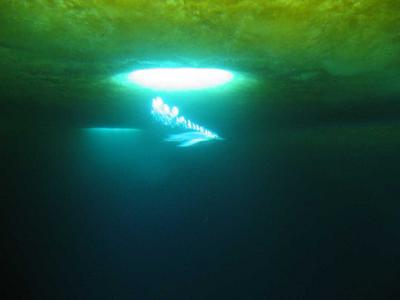

The best part of our visit to the Ranch was the chance to climb down

into the famous 'Ob Tube'. This 20-footlong and 3-foot wide tube is

set down through a hole in the ice near the penguin's corral. It's a

pretty tight squeeze in your bunny boots and thick parka-definitely

not a place for claustrophobics! One person at a time can climb down

the narrow tube and sit on a bench in a small viewing chamber under

the ice. This is as close as I'll ever get to diving under the ice.

What an incredible treat to sit there under the ice watching Emperor

Penguins drop through their hole and fly through the clear water in

front of you. The ice above was translucent, with a beam of light

shining down like a beacon through the hole. It was easy to see how

seals under the ice use that light to find their holes to return to

the surface.

Although we all felt like we could sit all day under the ice watching

the penguins, we knew it was time to let Dr. Ponganis and his crew

return to their work. It was time to leave the ranch and return to

Big Razorback, so we saddled up the snowmobiles and rode off into the

(non)sunset.

Daily Haiku:

Climb into the tube

View a world under the ice

Look at that penguin!

Dr. Paul Ponganis stands in front of the penguin corral.

Katsu Sato shows the sensor that he places on the penguins. The device has a small propeller in one end to measure acceleration as the penguin dives, as well as other sensors that record dive angle and speed.

Katsu demonstrates proper placement of the sensor.

Here's an Emperor Penguin ready to go swimming and record some data.

This is a view from within the Ob Tube. It was amazing to be able to watch the penguins diving and swimming.

Not every hut has its own seal!

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|