|

|

7 March, 1999

March 7, 1999

Greetings from Pine Island Bay! We've taken a lot of cores in the last 24

hours! The night shift took several piston cores during their shift, and

we started off with a piston core that was filled with glacial till. The

stiff sediments that we found tell us that the exact spot where we cored

was covered by an ice sheet at one time. We know this because till is

formed under glaciers. While we were just getting the core on the back

deck of the ship, a minke whale surfaced -- right at the back of the ship!

It was so close . . . and really neat! We were in and out of sea ice all

day today. Whenever there's a lot of ice, I especially like to look out

the portholes of the dry lab where we work. While watching the ice, I was

able to see lots of seals and penguins. It is really neat to look at, but

ice slows down our speed and makes it difficult to get good data on the

multibeam. All of the noise from crushing the ice makes it hard for the

sonar to work correctly.

I would like to spend some time over the next few days telling you about

some of the people I work with on the ship. The scientist in charge of the

day shift (when I work) is Ashley Lowe. Ashley is very excited that we are

finally in Pine Island Bay. She is a graduate student at Rice University

where she is working on a Masters degree in Geology. For her research, she

is studying Antarctic marine geology. Specifically, she is looking at the

stability of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. By studying the sea floor, she

plans to determine the retreat history of the ice sheet since the last

glacial maximum. Although Pine Island Bay is her major study area, she

will be comparing the Pine Island Bay region to Sulzberger Bay and the

Wrigley Gulf areas that we recently left.

Ashley is from Lincolnton, North Carolina. She is 24 years old, and she

graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a major

in Geology in 1997. Although it took Ashley a while to actually declare

Geology as her major, she has always enjoyed that parcticular field of

science. As a child, she had a rock collection and all of her science fair

projects always centered around geology. She began college as an

Environmental Science major with a concentration in Geology. After her

sophomore year (and before she even took a Geology class), the

Environmental Science program dropped its Geology concentration. Ashley

talked to members of the Geology Department and decided to declare Geology

as her new major. After one class, she knew that she had made the right

decision. For her Senior thesis, she worked with her professor to look at

long lines of depressions in the Blue Ridge Mountains and helped him

classify these lineations as fractures. She always wanted to attend

graduate school, but the right opportunities didn't seem to fall into place

after her college graduation. After talking with a friend who was at Rice

University, she called Dr. Anderson and set up a meeting. He wasn't able

to take another graduate student at that time, but he offered her a job as

his assistant with the understanding that she could begin working on her

Master's Degree at Rice University the following fall. Last year, Ashley's

two primary jobs were to help Dr. Anderson publish a book and to work on a

web page for the department's Gulf of Mexico research. She started her

Master's program this fall, and will graduate from Rice University in the

spring of 2001.

Now, let's spend some time looking at yesterday's question: "Where do you

suppose that we get fresh water for drinking, cooking, and washing on the

Nathaniel B. Palmer?" We get our fresh water by distillation -- which

means that salt water is boiled to separate the salt from the water. The

heat to boil the seawater comes from the engines. It seems that they get a

bonus out of the process -- the water is heated for distillation, and the

engines are cooled (which is a good thing)!

When the water evaporates, only pure H20 evaporates . . . leaving behind

all of the materials that are dissolved in the water (including the salt).

Those remaining materials are released back into the sea. The water vapor

is then cooled and condensed back into pure liquid water. In fact, this

water is so pure that we really shouldn't drink it. As a result, they

actually add chemicals at the bromide treatment plant before the water is

sent out through the rest of the ship.

This ship can make up to 13,000 gallons of water per day, but we are

averaging closer to 3,000 gallons per day during this cruise. For one

thing, we have a small number of scientists on board (only 9). In

addition, our research doesn't require the use of lots of water (and some

research projects do). We do use water to wash off our core barrels; but

the hose we use squirts sea water, so we don't have to use water that has

been purified. In addition, there are lots of ways that the ship conserves

water. For example, the toilets use much less water than a regular toilet,

and the showers all have low-flow shower heads. The two biggest uses of

water on the ship are the kitchen and the washing machines!

After the water is used, it goes down the drain . . . but where does it go

from there? We actually have a wastewater treatment plant aboard the ship.

All water (toilets, washing machines, dishwater, sinks, showers, drains,

etc.) goes to the treatment plant. They have something called an OmniPure

System aboard the ship, which uses a transformer to create a high amount of

D.C. (direct current) voltage. This voltage is used to electrocute the

wastewater -- which kills any harmful bacteria that may be living in it.

This is especially necessary because of the sewage in the water. Once the

wastewater has been treated, it is safe to release back into the ocean.

There is a holding tank that keeps the treated water until it reaches a

certain volume, and then it is discharged (about 4-5 times per day). This

is a very good method of treating water before it is released. It is

especially good that they don't have to use any chemicals to treat the

water (like most places do). We wouldn't want to dump any chemicals into

this fragile environment.

Since they are so careful about the Antarctic environment, what do you

suppose happens to the trash that is produced on this ship? What about the

trash from McMurdo Station? We'll look at that in tomorrow's journal! By

the way, we moved our clocks forward another hour today. Now, we are only

2 hours behind Indiana time! Thanks for all the email . . . I love the

questions and the journal topic suggestions!

Kim Giesting

Latitude: 73 degrees 23 minutes South

Longitude: 105 degrees 24 minute East

Temperature: -7.3 degrees C

Barometer: 969.2 mb

Wind Speed: 16.3 knots

Wind Direction: 222 degrees (from the Southwest)

Sunrise: 03:59

Sunset: 18:41

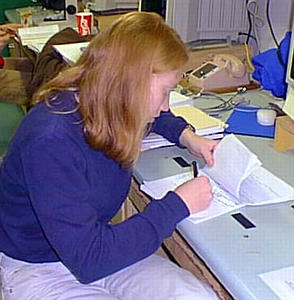

Ashley Lowe is working on her research proposal.

The night shift tooks lots of cores yesterday!

I saw a lot of Crabeater seals today!

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|