1 April, 2000

Bahia Paraiso

Question 42: How can you convert Celsius to Fahrenheit and vice versa?

Just visible above the surface of the water next to DeLaca Island is the

smooth curve of what looks like a whale. But it doesn't move. It is actually

a tiny portion of one of the southernmost shipwrecks. One that is only a mile

from the station.

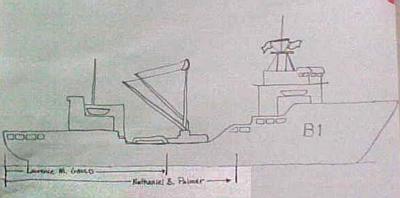

On the 28th of January 1989, the Argentinean supply/cruise ship Bahia Paraiso

ran aground after leaving Palmer Station. At almost 500 feet long, the Bahia

dwarfs both the Gould and the Palmer. She is now resting on her starboard

side parallel to the west side of DeLaca Island. For several days after she

ran aground on a rocky pinnacle, she stayed stuck on it, only slightly tilted.

Rough stormy weather eventually came in; and five days after the shipwreck,

the Bahia slipped off the pinnacle, came around the island and turned over

onto her side. The rest of the sinking process took place gradually over the

next few months, and for quite some time portions of the deck were still above

water.

The Bahia was carrying nearly 100 tourists that had just been ashore at

Palmer Station for a tour. The ship ran aground at 2 pm, and by midnight all

of the tourists had been picked up by other cruise ships in the area. Within

24 hours of the wreck, they were on land at Marsh Base (Chilean) on King

George Island preparing to fly home. The almost 200 crew members (ship crew

as well as change-over personnel for Argentinean bases in the area) spent a

couple of days at Palmer Station, living on spare floor space and in the

inflatable life rafts until they were picked up by other Argentinean ships.

Everyone involved was very lucky that the wreck happened on a flat calm, sunny

day.

More devastating to the ecology of the area, the Bahia was also carrying over

500,000 gallons of fuel (diesel or fuel oil) to resupply the Argentinean

bases. The fuel spilled into the sheltered marine environment of Arthur

Harbor and affected more than 28 square kilometers. A C-5 military cargo

transport aircraft was chartered to fly in an oil skimmer boat, its two

tenders and lots of containment material, mostly floating booms. The recovery

gear didn't arrive until 9 days after the shipwreck, and little of the light

fuel was recovered.

The Chilean naval vessel Yelcho came to investigate the wreck and to help

keep fuel from spreading. Their divers worked to patch some of the holes in

the hull. Science teams arrived a month after the spill to begin evaluating

the damage to the pristine coastal area that had 24 years of scientific

investment in it. Chuck Amsler was part of that research group and dove on

the Bahia many times. He recalls that the ship was still settling. The end

of the mast moved back and forth as much as eight feet when the water rocked

the boat. The stressed metal created loud groaning and creaking sounds

underwater and was very eerie.

Besides the inevitable effect on the marine ecosystem, one of the immediate

concerns of the station at that time was the possible contamination of the sea

water intake system (see 4/2 journal for more information about our water

system). It provides both fresh water for the people living at Palmer Station

and salt water for the aquarium tanks used by the science groups. Once

contaminated, it would have been virtually impossible to clean the station's

water system completely. Fortunately it did not prove to be a problem.

While the actual quantity of fuel was relatively small by global

spill standards, the timing and location of the oil spill intensifird its

effect on the ecosystem. The sheltered area of the harbor does not have

strong currents going through it to help the spilled material disperse, and

the spill occurred in the middle of breeding season for penguins and other

birds. Unfortunately, the fuel affected the invertebrate life very quickly.

Within weeks of the spill, station scientists observed huge die-offs of krill,

the shrimp-like base of the food chain in this area. Birds, seals and whales

depend on it as a major source of protein. Gastropods were also hit hard.

Limpets are the mainstay of Kelp Gulls which need them to raise chicks

successfully. Limpets and other gastropods in the area grow very slowly, so

this single event may have decreased the amount of some food items available

over a long period of time.

When we drive by the Bahia today in Zodiacs, only a 4 ft high, 24 ft long

crescent section of the bottom of the hull is visible above the water. You

can see the rainbow patterns on the surface of the water around it that show

the Bahia is still leaking fuel. On a calm day I could smell the petroleum in

the air. We will be diving the wreck of the Bahia Paraiso during our stay at

Palmer (4/13 journal).

Answer 41: The only difference is in the name. Centigrade was the original

name and expresses the basis of the scale. This temperature scale sets the

freezing and boiling points of water as the values of 0 and 100 degrees. The

interval is divided into 100 parts; centi- = 100, -grade = degree. The

political renaming of the scale to Celsius was done internationally in 1948.

A. Celsius was a Swedish astronomer.

The hull of the Bahia Paraiso by DeLaca Island.

Diagram of the Bahia with size comparison to length of R.V.s Palmer and Gould.

The Bahia Paraiso aground with tourists in life boats to the right. (photo courtesy of public domain 1989 home video)

All that is visible of the Bahia today.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|