|

|

13 December, 2000

The Weather

The south pole has a reputation for being cold. Really cold. Frigid,

even. The average annual temperature is –56.9 F (-49.4 C) and the record

low temperature at the south pole is –117.0 F (-82.8 C) recorded in June

of 1982. Since I got here a week and a half ago, the sun has been

shining, the sky has been blue, and the temperature has remained a fairly

constant –15 F. (-26 C.) Toss in some wind, and it feels more like –40 F

(-40 C). Which, if you are dressed for it, really doesn’t feel all that

cold. Before leaving Christchurch for Antarctica, parcticipants in the

United States Antarctic Program acquire two bags of winter clothing from

the Clothing Distribution Center in Christchurch. This includes

everything from long underwear and wool socks to a parka, hats and gloves.

Wearing this clothing, it is possible to be outside in these

temperatures, and much colder, without being cold.

This morning, when I was walking to the dark sector, I was immediately struck by the lack of blue sky. This morning was the first time I had seen more than a wispy cloud here and there since I arrived. Not only was it cloudy, it was foggy. In this image, Chris Martin is walking to the dark sector, just over 1/4 mile away. On any other day at the pole, it would be clearly visible in this picture.

Having the cold temperatures that we do at the pole, this was freezing fog: there was liquid water in the fog which then froze as soon as it came in contact with an object. The result of this was quite stunning, since everything now had ice crystal formations on them. The snowbanks, the flags marking the path, and even my hair by the time I got to AST/RO was coated in ice crystals. Since the freezing fog meant that there was increased moisture in the air, (the relative humidity was 100%, although the actual moisture in the air was quite low) it wasn’t good observing weather for AST/RO. With the weather being the talk of the day and not much happening at AST/RO, I went over to visit the meteorology folks.

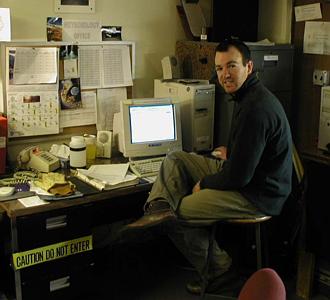

Dar Gibson and Nathan Tift are two meteorologists at the pole this summer. Dar is the senior meteorologist, shown here in the meteorology office, and Nathan is one of the meteorologists who will be staying here throughout the winter. The meteorologists at the south pole take measurements of the weather for meteorological records as well as for planes that are flying to the south pole in the summer. They take hourly readings of temperature, wind speed, wind direction, and pressure, among other things. Since it was cloudy today, and there were six flights scheduled to fly in, it was important to keep tabs on the conditions for the planes to land. The planes that fly into the south pole need a minimum of one mile visibility to land, so one of the things that Dar and Nathan were keeping a close eye on today was the visibility.

Periodically, Dar and Nathan go outside at see how far they could see. The clean air sector is 1/4 mile away, the dark sector is 1/2 mile away, and there are visibility markers 1, 2 and 3 miles away. At 11am, there was a plane that would be ready to land in 30 minutes. Dar and Nathan went outside to check on the visibility to see if the plane would be able to land, or if it should return to McMurdo. The clean air sector was in view, and the dark sector could barely be seen. So, we had slightly less than 1/2 mile visibility and the plane should not attempt to land. After circling for a few hours to see if the weather would get better, the plane eventually returned to McMurdo.

A few minutes after checking the visibility, Nathan released a red helium balloon. The balloon ascends at a constant velocity, so timing how long the balloon is visible tells us how high the clouds are. The neat thing about today’s weather was that it had cooled off; the temperature was around –20F most of the day, but that it felt much warmer than at any point in the last few weeks. This was because there was no wind. The wind contributes greatly to how cold it feels; taking the wind into account, you get a number called the windchill. This is based on how strong the wind is: a stronger wind, the colder it feels. Historically, the wind chill has been determined by putting someone outside and having them estimate how cold it feels, or seeing how long it takes a specific amount of water to freeze. Today, the windchill is determined by a standard table which has a range of temperatures and wind speeds.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|