|

|

8 March, 2000

Frequent Flying Picture

72 08 s, 118 55 w

-5 C (23 F)

Wind 24 knots (28 mph) from southeast.

Barometer 981 mb, steady

Depth 739 meters (2425 ft)

Ship headed generally northeast, following and mapping continental shelf edge

Stopping periodically for CTDs and cores

I woke up this evening and outside the porthole of my cabin it was

snowing heavily, big flakes of it passing by sideways in the deck lights.

Outside I could barely see beyond the rail of the ship, but I could tell by

the sounds of the SeaBeam pings that we were in about 600 meters of water.

From the clang of ice on the sides of the ship I could tell we were in

ack ice, medium sized floes of old, rotten multi year ice. Occasionally the

ship would lurch to one side or another, which told me there were some

bigger, more solid pieces. These push the ship around as much as the ship

pushes them.

I went down to the galley to midrats, to put something in my

stomach, and some coffee in my head. Being a cook on a ship must be

difficult. You have little space to work in, and that space is often

rocking back and forth. But I'm amazed at what the Nathaniel B. Palmer's

galley crew comes up with. Tonight it was Pizza, soup, pancakes, scrambled

eggs, grits, or oatmeal. Not to mention fresh baked bread, cookies and

doughnuts. The pizza was for people going off watch, not those just waking

up. I'm a big oatmeal fan. I realize that a lot of you are not, but I'm

sure you would find something here to look forward to. Feeding cold tired

people in Antarctica takes lots of planning and hard work.

After another cup of coffee I went up to the bridge to look around

and find out what was happening. The view from the bridge was like the view

from a car travelling in a snowstorm at night. The bright spotlights lit up

snow, and the visibility was only a hundred meters. The radar and the

SeaBeam could see much further though. The first looked miles ahead through

the snow, and the second looked a half mile below at the bottom.

Tom Kellogg was on the bridge, watching the SeaBeam output paint a

picture of the shelf break as we went along. We talked for while about what

he was learning on the cruise, and the questions he was trying to answer.

Scientists on board seem always willing to discuss science, which I don't

mind doing at all.

Speaking of seeing, let me show you a picture of a part of Antarctica

taken from space.

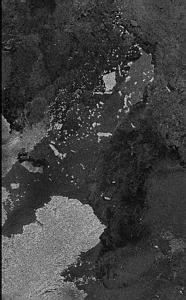

One picture with this journal looks like a black and white photo,

but it is really a radar image of the Thwaites Glacial Tongue and the

eastern part of the Bear Peninsula, taken by a Canadian Space Agency

satellite called Radarsat, an active microwave satellite. The picture you

are getting on your computer screen is just a degraded shadow of the

original. If you've ever photocopied a picture, then photocopied the copy,

and copied that copy, then you know what I mean. If you enlarge this image

on your screen, you will quickly see individual pixels, or squares. The

original image had very high resolution, and had the 94 meter (308 foot)

Nathaniel B. Palmer been in the area, it would have been detectable, and

you might have been able to pick out the lifeboats.

This image has been a long way in getting to your screen. The

satellite scanned the area, stored up the information, and perhaps sent it

to earth as it passed over Canada. The Canadians then sent a copy to Dr.

Shusun Li aboard the ship, via another satellite. They sent a slightly

lower resolution copy, because the original would have taken a long,

expensive time to send. I copied the image, and degraded it further, so I

could send it back over a third satellite, to Denver. From Denver it goes

out on the Internet to you. If pictures could get frequent flyer miles,

this one could fly for free.

Take a look at the image. It may help you to print this description and

have the image in front of you. The center of the picture is at about 74

degrees, 15 minutes south, 107 degrees, 0 minutes west. North is in the

upper right corner and south in the lower left. The biggest thing in the

picture is the Thwaites Glacier tongue (not the same as the now gone

Thwaites Iceberg Tongue) in the lower left. It is about 56 km (34.5 miles)

across. Halfway up the left hand edge of the picture you can see the

eastern part of the Bear Peninsula. The glacier tongue is floating, and is

some hundred or more meters thick. Notice the bay between the glacial

tongue and Bear Peninsula. From that bay extending almost to the upper

right corner of the picture you will see an area slightly lighter in shade

than its surroundings. This is the "fast ice" area I was talking about in a

recent journal entry. It is located where the Thwaites Iceberg Tongue used

to be. There is also an area of fast ice along the right hand portion of

the bottom of the image.

Notice that embedded in that fast ice area are a number of icebergs, large

and small. They look like little white chips. There are more icebergs here

than anywhere else in the picture. The largest one, in the upper central

portion of the image, reminds me of Indiana. I confess I don't remember the

exact shape of Indiana, but I think it looks like that iceberg. This berg

is about fifteen kilometers (9.3 miles) square, and is just to the left or

west of the fast ice area. Two other long thin bergs, maybe fifteen

kilometers long, are embedded in the fast ice between Indiana and the bay.

Many of these icebergs are probably grounded, although we cannot be sure.

In the area where the fast ice is we don't know the depth. Even a stronger

ice breaker than the NBP would have difficulty getting through the fast

ice. I know some icebergs touch bottom, because when ping editing I can

see the places on the bottom where current or wind driven bergs have plowed

the bottom sediment in long grooves.

The rest of the ocean shown in the images is relatively dark. Some

of this may be open water, some new ice, some pancake ice, and some floes.

You can see pack ice along the upper right edge of the picture, to the

right of Indiana. Sometimes it's hard to tell open water from new ice, and

rough water from pack ice. Looking at visual images helps interpret radar

images, if there are no clouds to block the scenery. Remember that

microwave satellites can see through clouds and at night. The work being

done aboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer by the "ice people" will help make

interpreting these microwave pictures easier and more accurate.

Just to the right (east) of Bear peninsula, in the left central

portion of the picture, there is a large, slightly darker berg the shape of

a stubbed out cigarette. North of it is a darker area, which could be new

ice or maybe open water. It looks like the berg has moved south through the

ice or the ice moved north past the berg. The second choice is correct. The

eastern (left) half of the bay isn't really fast ice, it is heavy pack. You

can see a faint dividing line between fast and pack. The pack ice has blown

northward past the grounded cigarette butt, leaving a "shadow" behind it.

A picture is worth a thousand words. You've gotten the thousand

words and the picture!

An update: I still haven't gotten the word on penguin's knees, but

I did find the missing sock.

Part of the Thwaites Glacier Tongue, as seen from a passing microwave satellite. The upper right part of the picture is where the cold tongue isn't.

A cold morning in the pack ice.

Jay Ardai operates a winch. Like many of the ship's support staff, Jay can do many different jobs. He can solve computer problems as well as get a stuck piston core apart, all in a day's work. The deck above his head is the ship's helicopter pad. The netting around the edge is there instead of a railing, which would interfere with the helicopter's landing approach.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|