29 May, 2000

Rock Ďní Roll Revival

May 29, 2000

Monday

Last night I was awakened by a loud KABOOM! in the middle of the night. I

bolted out of bed. "Susan! What was that noise?"

KABOOM! There it was again!

Susan rolled over in her rack (bed). "Oh, thatís just the waves crashing

against the bow. Itís nothing. Go back to sleep."

Susan has a lot more experience on ships than I do, since she spent a month

aboard the research vessel icebreaker Nathaniel Palmer in Antarctica last

year. Ship noises donít surprise her anymore. She rolled over and went back

to sleep. I got back in my rack, but I couldnít sleep. I lay there listening

to all the sounds on the ship. Waves crashed against the bow. The metal

drawers in our desk slid open and banged shut each time the ship rolled from

side to side. I felt like I was riding a horse that was galloping back to

the barn!

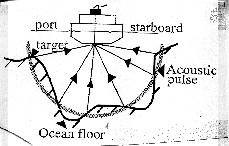

Pitch and roll make life on a ship interesting. They also create challenges

for scientists when they try to do their work. For example, imagine trying

to make a map of the ocean bottom from a ship. The sensors for the bottom

mapping sonar system on the Healy are mounted on

the underside of the ship. The sensors make a pinging sound that travels to

the bottom of the ocean and then bounces back to the ship like an echo. The

sensors record how long it takes each ďpingĒ to make the trip down and back.

The further away the bottom is, the longer the trip takes. In shallow water,

the trip is shorter. A computer records the data in the form of a three

dimensional topographic map that shows where the underwater mountains,

hills, and plains are located.

The problem is that every time the Healy rolls to the side, the sensors

move, too. That means that the ďpingĒ isnít always aimed straight down

towards the bottom of the ocean. Depending on the pitch (the movement of the

ship as it tips forward and back over the waves), and the roll (the movement

of the ship from side to side), the sensors might be pointing in a different

direction every few seconds.

Thatís why scientists use a special instrument called a vertical referencing

system. To understand how this instrument works, try this. Take a long piece

of string and attach some weights to one end. You can use washers if you

have them, but even a small rock will work. Now stand up and hold the other

end of the string in your hand so that the rock is just above the ground.

Hold as still as you can so that the string doesnít move. The weight of the

rock will pull the string straight down to the ground. The string is

perfectly vertical (straight up and down). You now have your own vertical

referencing system.

You can use this tool to tell if a picture on the wall is hung straight.

Just hold your string next to the side of the frame and compare. The string

will be vertical. Is the picture vertical, too, or is it crooked?

Sometimes this tool is called a plumb bob. The vertical referencing system

on the Healy is digital, but it works the same way. Just as the string tells

you if the picture is hanging crooked, this system tells the computer

whether the sensors on the bottom of the ship are pointing straight down or

if they are tilted to the side. Then the computer automatically adjusts the

data from the sensors. In that way, scientists solve the problem of pitch

and roll.

Now if only they could stop those desk drawers from banging, maybe I could

get a good nightís sleep!

To find out what an abyssal plain is, click on Susanís page:

Susanís Entry

Today.

DAILY DATA LOG (5/29/00):

Air Temperature: 2.2 degrees C / 36 degrees F

Latitude 51N

Longitude 50W

Sunrise 4:11 a.m.

Sunset 8:27 p.m.

This is the A-fram on the stern of the ship. Can you guess why they call it an A-frame?

You can see how the signals return to the ship.

This is the iceberg we saw today from the ship. It is pretty far off, but it looked big. Look in the middle of the picture on the horizon.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|