15 December, 1999

Cape Royds

I returned from my stint in the Dry Valleys early this afternoon. At 7:00 p.m. this evening, four of us took off on a skidoo adventure to Cape Royds to visit the Adelie penguin rookery. The piercing sunlight reflecting off the sea ice reminded me that back home in the Pacific Northwest, the sun had set before 4:30. It's great to have all this extra exploring time. To get to Cape Royds by skidoo, we traveled approximately twenty-five miles over frozen sea, past stark black islands with their perimeters sealed in ice. Although the air was still, racing at thirty-five MPH generated plenty of wind that sliced right into any uncovered skin.

My face froze the last time I rode a skidoo because I forgot to wear a neck gaiter and face mask. This time, I was much more prepared. I've just removed my face mask, which was getting sort of soggy from my breath.

On the way to Cape Royds, we stopped at a glacier frozen to the sea ice. It looks like nobody's home inside my parka, doesn't it?

Our fearless leader Ed was happy to see this iceberg! I wish I could stay here long enough to see if it will ever melt out this season.

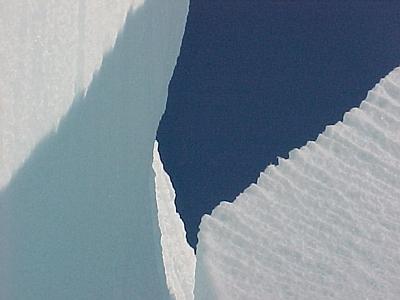

We spent a long time examining the iceberg up close. We had to be especially alert while walking around the edge, as there were places the sea ice was beginning to crack away from the berg. The various shades of white and cerulean were lovely against the bright evening sky.

Ice boulders have dropped off the upper surface of the berg.

The view through the far side of the crack that divided the berg in two.

Through the crack and around the side, I found these Weddell seals hauled out onto the ice. Although we were miles from the ice edge, they were able to make their way to the surface by coming up through widening cracks in the ice. They can travel impressive distances pulsing along slippery ice on their bellies. Here, they're basking in the sun, absorbing the concentrated warmth.

Cape Royds has a thriving Adelie penguin colony. Two members of David Ainley's research team are stationed among a few thousand Adelie penguins, studying the reproductive success of the birds here. The penguins mate for life, and return to approximately the same spot, year after year.

From where we sat perched above the colony, we had a great view. These penguins are briskly waddling across the sea ice. They can see another group of penguins off in the distance, heading towards them. When the leader got to the wide fissure, s/he paused momentarily, then leapt right over it.

When the two groups merged, there was a brief flurry of excitement. They all seemed as thrilled to see each other as long-lost relations. I sure wanted to know what they were saying to each other. When the hubbub died down, each penguin threaded through the crowd and the groups continued on their way.

The last of the stragglers, heading back to shore.

As the weather warms up over the next few weeks, these formations at the edge of the rookery will start to disappear.

I was surprised to see the Adelies squashed so flat on their eggs. It's an illusion, of course, due to their relative "necklessness", but amusing just the same. There was a lot of activity in the colony. Penguins are keenly alert to skuas, who are aggressive gull-like birds who would thrive on a meal of succulent chick. The penguins squawk at them noisily as they fly low overhead. Pebbles for nest building are in demand, and as we watched, Adelies would stiff-leg through the colony looking for some to snatch. If you look carefully, you can see star-like shapes radiating out from the nests. These are squirts of guano. The color ranges from white to pink, depending on what the birds have been feeding on.

Chicks have started hatching. Some of the penguins are sitting on eggs, others on hatchlings- soft grey tumbles of down. Adelie parents take turns going to the ice edge in search of the chance to dive for a meal. Until the big summer thaw, open water is still sixteen miles away. That's a very long walk! Like many seabird parents, they'll bring back partially digested food for their chicks. The chicks beg and peck in anticipation, and that stimulates the parent into regurgitating food directly into the chick's mouth.

These are my exploring companions. Carol Savage is a nurse practitioner from the clinic, Hiram Henry, a materials supply person from Crary Lab, and Ed Stockard is skidoo mechanic extraordinaire.

Cape Royds is also famous for being the site of Ernest Shackelton's hut. I was struck by the lack of windows, a practicality in the cold, and also by how new the wood looked after all these years in such an extreme environment.

I was disappointed that we didn't have the key to go inside the hut, but there was plenty to look at on the outside. The mens' canned food supply was neatly stacked along the outer walls of the hut, just as they left it almost ninety years ago.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|