5 December, 1999

For Thomas B, Orcas 5th grader

Like most people who come to the Antarctic, I hoped to see penguins. Since I work a long way from where they live at the edge of the ice, I knew my chances weren't good. Then, a few days ago, due to a fortunate series of coincidences too convoluted to go into here, I discovered that a man I knew when I worked for U.S. Fish and Wildlife in Hawaii was here at McMurdo working as a member of Paul Ponganis' Emperor penguin research team.

Greg Marshall works for National Geographic Television in Washington, DC. He and his partner Birgit travel around the world assisting biological research projects with video technology they developed. They help biologists see how animals make their living underwater. When I met Greg in the summer of 1997, he was busy attaching "Critter Cams"(small, remote video cameras encased in waterproof housings) to the backs of endangered Hawaiian Monk Seals. The pair work on projects with all sorts of marine animals- humpback and blue whales, tiger sharks, a few species of seals, sea turtles, and now Emperor penguins. This was Greg's first season using his Critter Cams with penguins. Once a camera is attached to a penguin's back, the research team members can track its behavior under water from the bird's eye view. Greg headed back to New Zealand this morning, but before he left, he arranged for me to make a visit by skidoo to the ranch before the penguins are returned to the sea tomorro!

w.

Paul Ponganis' research project focuses on diving physiology and feeding behavior in Emperor penguins. Each season, his team brings a dozen or so birds in from the edge of the sea ice, and holds them in a corral for a short time so they can learn more about them. There are a number of dive holes cut into the ice within the corral. Since the penguins are so far from open water, once they take their first dive, they quickly figure out that they need to return to the same group of holes to get out of the water. Living so far away from the ice edge has a temporary advantage- a predator free environment.

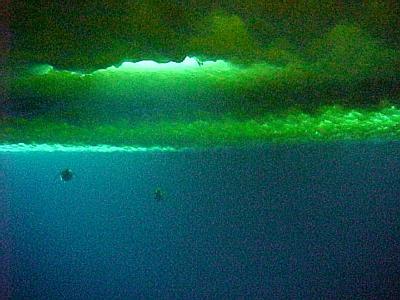

When I got to the corral, I was startled at how beautiful the penguins were. All the photos I had ever seen did nothing to prepare me for the presence of these birds. There were thirteen of them, placidly waiting in line to dive. What would it be like to watch them swim, I wondered? It turns out, the researchers had recently inserted a metal observation tube through six feet of sea ice, which then extended another ten or fifteen feet below the lower surface. When I first looked down the tube, it seemed narrow and dark and a long way to fall to the bottom. It was just a bit wider than the width of one large person. I knew I wouldn't forgive myself if I didn't go down there, so I pulled off my bulky parka and made for the ladder. The hardest part was figuring out where to place my first foothold. Once I started down, I found I could wedge myself into the wall of the tube for extra balance. Soon after I began to descend, someone up at the top closed the lid. Now, the only light t!

o see by came from the dull glow of daylight filtering through the golden underbelly of the ice. I inched my way along the innards of the tube, stretching each foot down into the darkness to feel for the next step. When I reached the bottom, there was a small bench wide enough for two. Tall windows wrapped around to allow a wide-angle view. In this surreal landscape of total calm, the world was distilled into dark patches of ochres and blues with occasional flashes of penguin light. I could have stayed down there for hours.

"Rancho Penguino" is ten kilometers from McMurdo and sits out on the sea ice 20 kilometers from open water. This is the largest building. There are a few smaller sheds and an outhouse. The researchers sleep in tents on the ice, surrounded by drifting snow.

The researchers sleep in tents on the ice, surrounded by drifting snow.

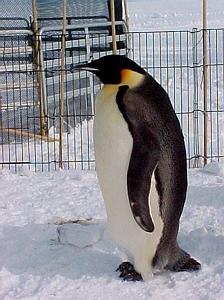

Emperors are the largest penguins. Where white meets amber on their chests, the feathers shimmer in the light like jewels. These birds are truly regal!

I was amazed at how calmly they lined up for the dive hole. I watched them wait in a perfectly straight line for a long time. Somehow, they work out who stands where, without too much conflict. (For my students back home: Think like Emperors!)

The penguins with their heads tucked down are preening their feathers.

This photo gives you a sense of how short penguin wings are, relative to stocky body size. What they lack in length, they make up for in strength. They use their wings like humpback whales use their pectoral fins. In both cases, well-developed chest muscles power underwater 'flight'.

The birds slide onto their bellies as they approach the dive hole, then plop in head first and swim.

These two penguins are getting ready to leave the hole. They'll use their beaks as an extra appendage to hoist themselves out.

The many minutes I spent sitting in the observation tube were some of the most memorable of my life. There were long moments of quiet, then penguins would shoot through the holes and silently glide by. This photo was taken with a video camera and downloaded to a still image by Ed Stockard.

I shot many photos while I sat in the bottom of the tube. My flash kept going off automatically and reflected bright streaks on the glass. This is the only photo that turned out. Notice the golden color on the bottom of the sea ice.

Photograph by Ed Stockard

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|