8 August, 2002

Yesterday (I'm writing this on August 9) seemed like a very long day!

Things started well when I got up early to write the journal for the 7th.

The journal was almost done when my computer, which had been acting

strangely for a few days, suddenly froze up. After shutting it down and

restarting it, it closed itself down and gave me a screen-wide error

message. After I shut it down and restarted it one more time, it shut

itself down again and would not allow me to re-boot (start it up again)!

Knowing that all my journals and photos were saved on the hard drive, I was

very nervous! Two wonderful people, Steve Roberts and Sean Kuhn (I'll tell

you about each of them in an upcoming journal), spent several hours working

on it and they managed to get all my files backed up onto the ship's

computer. My own computer is running again, but doing strange things

periodically, so I will continue to back up all my files daily using the

ship's computer. The lesson for today is - always back up your important

files on a regular basis.

Our sediment sampling started at 4:45 PM and we wrapped up our work at 1:45

AM. It was a difficult station because the station is right on the slope

which drops off sharply to the basin. Whenever the ship is stopped for

sampling it drifts. Usually that isn't a problem because the depths don't

change that quickly. But, due to our position on the slope we had to

re-position several times to be certain we were sampling at the correct

depth of 500 meters. In addition, the mud was soft, making it difficult to

get a good core sample. Jackie is not one to give up, and we kept trying

until she had the samples she needed. At one point in the evening we

stopped for yet another amazing organism in one of Jackie's samples. You

often see pictures of coral reefs with brightly colored anemones attached to

the coral, waving their tentacles into the water above them. Jackie had

found a beautiful, orange colored anemone in the sediments at 500 meters!

One other note - around midnight, the skies began to clear for the first

time in several days. As the sun broke through the clouds the ice seemed to

glow with light; it was spectacular!

After a few hours rest, I got up this morning to talk with Ev Sherr and

Jennifer Crain. Ev is a professor of oceanography at Oregon State

University in Corvallis, Oregon where Jennifer is a science technician. We

all admire Jennifer because she is one of a handful of people who were on

the SBI spring cruise and who, after a brief three weeks at home, returned

for the SBI summer cruise. Remember that each cruise is 40 days long! Ev

and Jennifer are working closely with Carin Ashjian, Bob Campbell (he came

on board about a week ago) and Stephane Plourde to study the structure of

the plankton food web. If you check the journal from July 27, you'll find

the diagram of who eats what among the plankton. Remember that

phytoplankton are the plant plankton and zooplankton are the animal

plankton. Carin and Bob are studying the grazing rates of the

mesozooplankton (larger ones), and Ev and Jennifer are studying the

microzooplankton (micro = tiny). Both types of zooplankton eat the

phytoplankton, and the mesozooplankton also eat the microzooplankton (check

the diagram in the July 27 journal). The microzooplankton are extremely

small and most are in a kingdom of unicellular organisms called Protista.

If you've ever looked at pond water under a microscope, you've probably seen

examples of protists swimming around.

While Carin and Bob are looking at the grazing rates of the mesozooplankton,

Ev and Jenn are looking at the grazing impact of protists (microzooplankton)

on phytoplankton. In order to do this, they take large amounts of water

from one depth. They choose a depth that is in the euphotic zone (light

reaches there) where they are certain that there are lots of phytoplankton.

They concentrate on the innermost stations (shelf) and outermost stations

(basin) in each transect. Once they have their water, Ev and Jennifer

dilute it several times with filtered water before they incubate it (put it

in an environment where things can grow naturally) in two large tanks on the

bow of the ship. They do this to make it more difficult for the grazers

(protists in this case) to feed on the phytoplankton. Each incubation tank

contains eight cylinders and each cylinder contains 2 large bottles of

water. Each cylinder is wrapped in a special plastic to mirror in situ

(natural) light levels. The incubation takes three days because the water

is so cold that life processes are very slow.

Both before and after incubation, Ev and Jennifer sample the water for

chlorophyll. Since phytoplankton contain chlorophyll, these chlorophyll

measurements give them an idea of the change in the numbers of phytoplankton

over the three days. Using that information, they can calculate the growth

rate of phytoplankton both with and without grazing (other organisms eating

them). For the last part of their work, Ev and Jennifer filter their water

to remove the protists and use a special stain in order to view them using

epifluorescence microscopy. That means they use a specialized microscope

where the light comes from the top (epi).

Stop and think about the big picture for just a minute. Phytoplankton are

the base of the ocean food web. Both micro and mesozooplankton eat them,

and mesozooplankton also eat the microzooplankton. Now think about an even

bigger picture. Zooplankton are eaten by fish which are eaten by seals

which are eaten by polar bears! Maybe now you can appreciate why it is so

important to understand the ocean food web (who eats what) at ALL levels.

<> Ev Sherr is a professor of oceanography at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon. On this cruise, she is looking at the grazing impact of protists (microzooplankton) on phytoplankton.

<> Jennifer Crain is one of a handful of scientists who are on both the SBI spring and summer cruises. She's working with Ev on the grazing impact of protists on phytoplankton.

<> Ev and Jennifer incubate their samples for three days in two large incubator tanks on the bow of the ship.

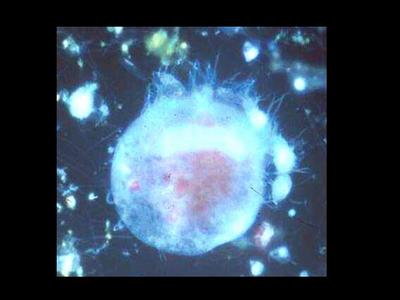

<> This is a ciliate (a type of protist) that you might find in the Arctic Ocean. The red color that you see inside is from the phytoplankton it has eaten. The picture is taken through a microscope. You can't see these organims with the naked eye.

<> Jackie found this beautiful anemone in one of her respiration experiments. Although it is like the anemones you see in pictures of tropical coral reefs, this one lives 500 meters down in the cold Arctic Ocean.

<> Around midnight, the sun finally reappeared for the first time in several days.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|