|

|

17 October, 2003

We awoke to a bluebird morning-clear blue skies with Mt. Erebus

towering over the eastern horizon. My first night spent sleeping in

a converted refrigeration box (these sleeping huts began their lives

as semi-truck refrigeration units) went well. I had a comfortable

and toasty bed. We slept with the heat turned down low and the door

slightly ajar-otherwise it would be way too hot. It's about -15C

outside-and almost 22C inside our kitchen hut. Life is good.

It was finally time to learn the fine art of seal tagging. After

breakfast we set out to meet the neighbors-there are two groups of

seals within walking distance of camp. We gathered up our tools; a

daypack with seal tags, sets of tagging pliers and hole punches,

handheld computers, and a notebook for recording a hard copy of our

tagging data. It's also a good idea to wear gloves that you don't

really value too highly, since they get covered with the essence of

seal. In addition we take a seal bag-a conical piece of heavy fabric

about a meter long with 2 looped stout ropes affixed to the sides and

breathing holes at the narrow, or nose, end. While baby seals are

easy to tag without much physical effort, tagging adult seals

requires a more aggressive technique.

While Kelly, Mark, Brent, and I watched, Gillian and Darren showed

how to place the tags in the special tagging pliers and went over

some of the more common pitfalls involved in tagging. It is

important to have the two sides of the tags properly aligned in the

pliers so the post that holds the two sides together doesn't bend or

break. Tags are placed in both rear flippers, in the web of skin

just in from the 'little toe' area. In baby seals the web is thin

enough to allow you to place the tag using only the pliers. In

adults, the web is so thick that you must first punch a hole using a

leather punch and then place the tag using the pliers.

Once tags are firmly affixed to the flippers, it's time to record the

important data. In the field notebooks we record whether the animal

tagged was an adult or pup; in addition, we write whether it was male

or female. We also note whether it has any relatives-in the case of a

female that would be its pup. For example, an adult female with one

pup would be listed as AF1. We also write down its tag number,

usually a 4-digit number followed by the letters 'AA'. The tags are

yellow (noted as A, for amarillo-yellow in Spanish). By writing 'AA'

we know that there are 2 tags with that number-one in each flipper.

We mark down the location and whether it is a new tagging or

re-tagging-seals with missing or broken tags must be re-tagged. Once

all this is done, we enter the information in our handheld computers.

This data is downloaded each evening into a laptop computer.

This might sound relatively straightforward, but it all gets somewhat

more interesting when you add the following factors to the equation:

it's cold, the wind is probably howling, you're standing on a

slippery surface, there's open ice cracks in the vicinity (that's how

those seals got there), and the adult seals do not sit idly by while

they are handled.

Tagging the pups is relatively straightforward. One person uses a

bamboo pole with a red flag at its end to distract the mother, kind

of like an Antarctic version of a matador. By waving the flag in the

mother's face, you can get her to move away from her baby. While she

is busily barking in the direction of the flagger, the tagger steps

in, holds the wriggling baby seal as tightly as possible, and affixes

tags to each rear flipper. The tags have sharp rubber points to go

through the flipper, and these are snipped off after they are applied

so they do not irritate the seal. It all might sound simple, but it

makes you wish you had at least one extra arm to hold down the baby.

Tagging adult seals is a bit trickier. This is where it really gets

exciting and the seal bag comes into use. Darren and Gillian

demonstrated proper bagging technique. You grab the seal bag firmly

by its side ropes, hold it behind your back, and just below your head

and slowly approach the seal. When you are alongside the seal you

whip the bag over your head towards the seal and, hopefully, end up

with it over the seal's head. Then the dance begins, as the seal

tries to back out of the bag and you straddle it trying to keep the

bag over its head until it calms down and lies still. If all goes

well, the seal will soon tire of this game and lie calmly on the ice

while you punch a hole in each rear flipper and apply the tags.

Darren and Gillian made it look relatively easy-but it was obvious

that it was much harder than it looked.

We returned to our camp for snacks and hot beverages, and set off on

the snow mobiles to look for seal pups and apply our newly learned

tagging, bagging, and recording skills at a colony near Tent Island,

about 15 minutes away. We split into two groups, and worked our way

along one side of the island. Our group encountered 2 female/pup

pairs-both females were already tagged from previous years, so we

only needed to distract them while we tagged their babies. I was

able to try my hand at the seal bag dance with an adult male that had

broken tags. When tags are broken, they need to be removed and

replaced with new ones. Gillian attempted to distract him with the

red flag, while I stood with the bag, waiting for just the right

moment to get it over his head. He was positioned next to a large

ice crack and used this to his advantage, crossing back and forth

after each unsuccessful bagging attempt. In the end it was 'Seal 1,

Susy 0' as he reached a diving hole and disappeared under the ice.

Bagging the seals definitely takes practice. I've never danced with

a 1000 lb animal before-it just takes time to get the steps right.

Over the next few weeks I am sure I'll have ample opportunities to

practice.

Why are we dancing with seals? A primary focus of this project is to

study the demographics of the Weddell Seal population. To do this,

you need to have a method for tracking individual seals. Tagging

animals and tracking them over a long period of time will give you

information that can help you determine longevity and survival as

well as the number of pups born each year and the ratio of males to

females in the population. Scientists have been studying Erebus Bay's

Weddell Seal population for over 34 years. During this period, over

15,000 animals have been tagged. This year's project will add to

that database and provide information that will allow further

analysis of this population.

Daily Haiku:

Weddell Seal tagging

Dance with a thousand pound seal

Watch out for their heads

Darren selects a tag

Tagging a pup

Approaching the seal

Over the head

Darren holds the seal while Gillian places tags in each flipper

The view from camp--Mount Erebus, the southernmost active volcano

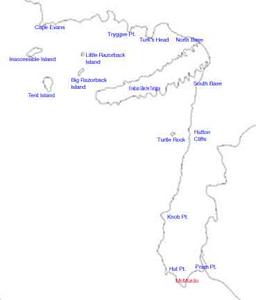

A map of our study area

Darren demonstrates the fine art of seal bagging

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|