|

|

27 October, 2004

Cape Chocolate at Last!

The bad weather that kept us from flying yesterday was gone this morning. The sky was clear and the air was still. Beautiful.

Stacy, Kathy, Jennifer, and I were on the first of the two helicopter flights at 9:00. With most of the remaining items that needed to fly out, we took off in the helo and flew west across the ice lit with bright morning sun.

The sling load that was carried by helicopter two days before was near the site where we were going to camp. Nick, the helo tech who helps with cargo, passengers, and safety on the flight, told us that we should remove the nets from the sling load and have them rolled up and ready so they could be picked up when the next flight came back with Mike, Andrew, and Bob.

After we were dropped off, we busily moved all the gear that needed to go to the dive site, which was about 100 yards from the camp site (more or less - my distance estimation is not great). Some of the things we had to move were bags of dive gear, wooden boxes that each contained two scuba tanks, a big Scott tent, fuel, a sled, shovels, dip nets, and kitchen gear to go. Sleep kits - bags that contained our sleeping bags and sleeping pads - and tents were left at the camp site.

The blasters had been out two days before and had blasted two holes in the ice - one for the main dive hole and one for the safety. The area that had been blasted was quite large - a crater at least 15 feet across for the main hole. It was harder to come out two days after the hole was blasted, because the hole had frozen over with up to a foot of ice in places.

The second helicopter brought Bob, Mike, and Andrew, and the Hotsy. The Hotsy is a machine that heats glycol to 210 degrees and runs it through long hoses and then a metal coil. The coil is lowered into the dive hole-to-be and, over the course of hours, melts the hole to make it bigger. This usually needs to be supplemented with chipping and dipping, too.

Once everyone was there, we started setting up the tents. The big Scott tent went near the dive hole so the divers could change - remember there is really no source of heat at this field camp other than what our bodies generate and our clothes keep in! Four two-person "mountain tents" were set up at the campsite. After some confusion with where the four tent poles, 16 clips, and 12 fly buckles go, Stacy, Kathy, and I were on our way to comprehending these award-winning architectural structures, and Andrew went about securing them to the ground with deadmen, warthogs, and ice screws. Sounds pretty strange, but they're pretty simple. Deadmen are short poles that get buried parallel to the end of the tent with a line tied to the tent. Warthogs are metal spikes with teeth that go down into the snow and attach to a line that holds the tent down. And ice screws are....well, screws that go into the ice. The main way they differ from the screws we use is that they are hollow, so sno

w or ice goes up inside the screw too.

Once our shelter was ready, it was time to open up the dive holes. This is very hard work. Tools used include a chainsaw, breaking bars or chipping bars (long, fairly heavy steel poles with narrow blades on the end), ice tongs, dipnets, and lots of sweat. The person using the chainsaw has to wear raingear - in this case, fur-lined - because the water comes spraying up like a fountain while they cut. You might think that it would be easy to cut with a chansaw but in fact, it's very difficult and exhausting. It took a few hours with people taking turns on chainsaw, tongs, and chipping bar to get the hole opened again. Andrew took one parcticularly enthusiastic lunge to chop the ice and the chipping bar slid right down into the dive hole, even though he had the safety leash over his wrist.

Kathy kept everyone fed with a delicious lunch of soup, cheese and crackers, wasabi paste, hot pepper sauce, smoked oysters, hot drinks, and of course, chocolate.

After the hole was opened, Mike looked in and saw chunks of ice down below. They were still attached, but he was concerned that they might come off. If big chunks of ice came loose while the diver was underwater, the hole could be blocked and the diver could be trapped until people on the surface could remove the ice. We started poking hard at the ice and, sure enough, some huge chunks started coming up, along with lots of smaller chunks. We continued to poke at the ice, mostly using a bamboo pole now, until no more ice came loose. This process had opened up the hole a lot, made a nice wide place for the divers to go down, and exposed beautiful blue-looking chunks of ice beneath our feet all around the hole.

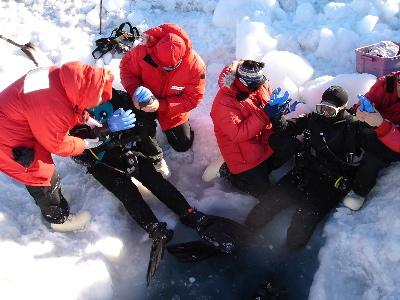

Finally, later in the afternoon, everything was ready and it was time to dive. Andrew and Stacy put on their dry suits in the Scott tent. Jennifer reminded us that, when the divers are entering the water from an unheated environment like this, it's really REALLY important to help get them ready FAST ! We had to keep their fleece liner gloves and their diving masks inside our jackets, next to our bodies to keep them warm. This is especially important for the mask, because if it freezes up on the inside, the diver can't see.

As they slide into the water, I thought once again that I would love to see what was down there, but I wasn't sure how I would do with going in and coming out of the dive hole onto the exposed ice. Stacy was colder than usual when she came out. However, they had taken six core samples and seen scallops, which are found on this side of the sound, as well as very large anemones, and brittle stars. Stacy was surprised to see siphons from the Laturnula clam as well. Andrew was even able to retrieve the very elusive Antarctic species, Chippus barus, from the sea floor where it had fallen.

Now that the samples were taken, Jennifer, Kathy, and Andrew had to figure out a way to sieve the samples as they do in the lab. They used the safety hole - with the warmer water because the Hotsy was down in it. The water in the tube of the squirt bottle kept freezing, providing an additional challenge. Scientists often need to be creative and persistent in Antarctica in order to meet their research goals and especially to maintain the same quality they would have in a much more convenient lab situation.

When the sieving was done, it was time for dinner - backpacker's instant dinners. Pour the boiling water into the bag, stir, keep the bag in your jacket for 10 or 15 minutes, and - voila! Dinner is served. I had Santa Fe red beans and rice. It tasted pretty good. To give you an idea how many calories are needed when working outside in these temperatures, most people ate two of the dinners. They are supposed to each serve 2 people! You need a LOT of food to meet your energy demands and to keep warm.

At about 10:00, we walked up on top of the little island we were camped next to. It's made of lots of small dark volcanic rocks, almost like huge dark sand grains. Bob found a dried light brown ring of shaggy-looking stuff. Stacy said it was an algae; this type of algae will start to grow as the weather gets warmer! This kind of thing is about the closest you get to a plant in Antarctica (not counting the kitchen greenhouse at McMurdo, of course).

The island was surrounded with pressure ridges of ice pushing up in the air. Their tops had been eroded and were sharp. In some places, they almost looked like teeth. These were incredibly beautiful, catching the light before the sun dips below the mountains. Although the sun no longer sets, it does get low enough to go behind high areas such as mountains. It was a gorgeous time of day, and everything around me was magical, from the softly sloping black island, to the ice peaks of the pressure ridges, to the Hobbs Glacier coming down the mountain on the other side of Salmon Bay, to the total quiet broken only by little cracks and sighs of the sea ice under our feet, and the views of Mt. Erebus and Mt. Discovery on opposite ends of our range of view.

In addition to being breathtakingly beautiful, the walk served to warm us up before crawling into our tents. Kathy was already sleeping when I entered the tent, but my winter camping bedtime routine probably woke her up: Unzip the vestibule on the outside. Zip the vestibule. Unzip the tent. Remove boots outside, but knock off snow and bring them in. Brush all snow off pants. Zip tent. Remove parka and put it over the feet of the sleeping bag. Change hats. Remove liners from boots. Put liners inside fleece sleeping bag liner. Put water bottle in, too. Put one of the fleece jackets and pair of gloves into sleeping bag. Change socks. Put camera in sleeping bag. Put granola bars in pocket by head if needed to warm up during the night. Slither into fleece liner. Zip liner. Zip sleeping bag. Fumble around for string to pull sleeping bag hood closed. Ready for sleep at last! Zzzzzzz

1. Jennifer and Stacy are on the way to Cape Chocolate at last! Yippeee!

2. Kathy snaps a picture of the helo while standing next to the sling load of equipment.

3. Hauling equipment to the dive site.

4. Setting up the tents.

5. The Cape Chocolate camp. The Scott tent, with the dive equipment and outdoor "kitchen" is in the foreground. The chucks of ice on the ground are from the blasting of the dive hole. The four sleep tents are in the background.

6. Chainsawing through the ice is hard work and very wet.

7. Bob and Stacy prepare the coil of the Hotsy to go into the water.

8. Get those gloves on QUICKLY!

9. Fine dining, field camp style. Seconds, anyone?

10. The sun shines over mountains in the distance and through pressure ridge ice up close.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|