18 February, 1999

February 18, 1999

Greetings from the Ross Sea! The night crew had news for us as we arrived

downstairs this morning. While they were taking a core last night, the

temperature reached -22 degrees C! Since we have been here, that's the

coldest

temperature that we have seen. Their core site was located right next to the

ice shelf, and the cold winds blowing off the shelf probably had something to

do with it. Today, we had a very busy day! We took three cores, in addition

to doing multibeam surveys. When we take a core of sediments from the ocean

bottom, do you suppose that the oldest sediments are at the top of the core or

at the bottom of the core?

Yesterday's question was "Do you know how sonar works?" Sonar sends

"pings" of

sound down through the water. We can actually hear these pings throughout the

ship -- they sound like the chirp of a small bird. These sound waves travel

from the source of the sound to the bottom of the ocean and back up to a

receiver. Computers analyze how long it took for the sound to travel that

distance, and by using that information (as well as things like the water

temperature and salinity) they can determine the distance to the bottom. This

is the same basic way that a fish finder works. Scientists look at the bottom

of the sea floor to find evidence of the glaciers (moraines, scratches from

icebergs, etc.). We have been using equipment to look at the bottom of the

sea

floor constantly. In fact, we have four different machines that each do this

job in slightly different ways. We have one piece of equipment called a

multibeam. This is the one that I have mentioned the most. This is attached

to the underside of the boat and it sends pings of sonar to the right and left

as well as straight down. With this instrument, we can make a contour map

that

shows us what the bottom looks like.

When I mentioned that we had to edit some of our data, we are editing the

multibeam data before the contour map is drawn. Sometimes the pings don't

make

it all the way to the bottom due to things like rough water, reflection, or

refraction. We have to edit each set of pings on the computer and erase any

wild points. It takes about an hour of editing for every hour of data. You

would think that a computer could do this job, but according to our support

staff there are no computer programs that do it as well as people themselves.

Almost all of the ASA staff do ping editing, as well as all of the scientists

except Dr. Anderson. Each day, we have two sets of data to edit. If we

have a

chance, we edit at least some of our data while we are on shift. If the

day is

too busy, however, we will finish our ping editing after our shift is over.

Another instrument that depends on sonar is called the Bathy-2000. It also

sends out pings of sound, but they are at a slightly different frequency.

Because of this, they can go down a little bit into the sediments. In other

words, this instrument can not only show us what the bottom looks like, but

also it can show us what the top layer of sediments looks like (layering, for

example). Whereas the multibeam shows us the contour map of the bottom, the

Bathy-2000 shows us a side profile of what's beneath us. We watch the

Bathy-2000 a lot when we are determining where to take a core. We want to

make

sure that the sediments we are coring are made of mud and not solid rock!

The third instrument that uses sonar is called the Simrad. When biologists

are

on board, it truly is used as a fish finder. We monitor that it is up and

working, but we don't rely much on it's data. If the Bathy-2000 crashes, the

Simrad is a backup (but it has much fewer details). These first three

machines

are running all of the time on the ship. Every 15 minutes, when we walk

around

and take our log, one of the things we do is check each of them and make sure

that they are working properly. Being computers, they have a tendency to

crash

just like our computers at home. If the screen freezes, we aren't collecting

any data! So why do you suppose that we walk around and check every 15

minutes

instead of once each hour?

Our last instrument that uses sonar is called a "deep tow." This instrument,

however, is not attached directly to the boat. We pull it behind the boat

by a

long cable. The "fish" hangs in the water and sends out chirps of sound,

which

travel down through the water to the bottom. The sound waves that come from

the sides of the fish go down at an angle (like the sides of a triangle) and

make a map of the bottom (a top view). The sound waves that go straight down

actually penetrate the sediments. They are used to make the profile (or side

view) of the sediments. The readings are recorded digitally on a computer as

well as visually on a printer. Like the Bathy-2000, this instrument is used to

look at the top 10 meters of sediments. This biggest difference is that the

deep tow gives us a much clearer picture with a lot more detail. The deep tow

can see things that are 10 times smaller than things that can be seen with any

other sonar instrument on the ship . . . it can map things that are only one

meter (about 3 feet) across! That's not too bad, considering we are

working in

anywhere from 500 to 1200 meters or water! Since the deep tow is not

permanently attached to the ship and has to be placed in the water, the

scientists are very selective about where and when we are using it.

Unfortunately, our deep tow isn't working right now. There are several people

on the ship who are working very hard to try and get it fixed. Hopefully,

they

are making some progress and we'll have it up and running in another day or

two.

Well, it's getting late and I really need to sign off for the night. Keep

those great questions coming! I'll be back tomorrow!

Kim Giesting

Latitude: 76 degrees 52 minutes South

Longitude: 170 degrees 01 minutes West

Temperature: -6 degrees C

Diane is ping editing some mulitbeam data.

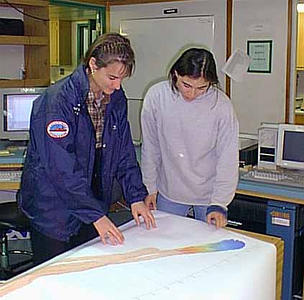

Suzanne and Tamara are looking at a contour map made from the multibeam data.

Kim is saving the Bathy-2000 files.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|