20 August, 2003

In the history of Arctic exploration, one pioneer stands above all

others in creativity, intellect, and sheer daring: Fridtjof Nansen.

A distinguished scientist considered being one of the founders of

oceanography; he set out in 1893 to demonstrate the existence of a

trans-polar current in the Arctic Ocean. Nansen's plan to

intentionally beset his ship, the Fram, into the ice and drift across

the North Pole was spectacular, if not reckless. After two years

drifting in the ice, Nansen's restlessness got the best of him. He

decided contrary to his original theory that his ship would not pass

over the pole, so he and another shipmate set out on skis. His

journey "farthest north" (86 degrees of latitude) is forever etched

into the annals of heroic adventure and scientific discovery.

Although Nansen's brave exploits often eclipsed his scholarship to

the public, scientists will always remember him for his contributions

to science and history. From his soundings of the ocean bottom while

he drifted on the Fram, Nansen discovered the deep water of the

Arctic Basin which had previously been thought to be relatively

shallow. He also first described what later became known as the

Ekman spiral, named for the mathematician that quantified Nansen's

observed deviation in the layers of seawater due to the earth's

rotation. Later he explained the "dead water" phenomenon (i.e.

standing waves where fresh water lies on top of salt water) that was

first described in Roman times. And Nansen was an inventor too. He

developed a reversible bottle for taking deep seawater samples which

was later modified by Otto Petterson. Now known as the

Nansen-Petterson water bottle, it was used by oceanographers around

the world until very recently. He went on to investigate the

variable currents of the Gulf Stream. Finally, Nansen's work The

Norwegian Sea was the first comprehensive treatise of any sea, and

his book Northern Mists remains required reading for students of

Arctic exploration history.

So in this spirit of scientific adventure, it's not much of a stretch

to put the scientists and technicians aboard the research vessel

Nathaniel B. Palmer in the same boat with Nansen. For starters, the

Arctic Ocean is probably the least known region on the planet. (The

Antarctic continent by contrast has a permanently-based group of

scientists working at the South Pole Station.) And it is modern day

explorer-scientists like Dr. Jim Swift that are hard at work in

probing its secrets. Sure, even though the Palmer is a far cry from

the Fram, and the Chief Scientist's room is somewhat more comfortable

than Nansen's cabin, the general purpose of each cruise hasn't

changed; that is, making the unknown known.

The methods and technology used by today's oceanographers are

different, of course, but the scientific exploration of the Arctic

continues onward in much the same manner as in Nansen's day. The

discovery of the westward flowing current during the cruise's last

cast, for example, may not be unlike Nansen's Ekman spiral which

represented a new contribution to the field of fluid dynamics. Could

this west flowing river in the sea be a major new mechanism for

moving waters from the continental slope en masse into the basin

interior? Maybe the answer will reveal itself in what Jim Swift

calls an "aha" moment. That's when the light bulb turns-on in the

mind's eye and the key to understanding some phenomena becomes

crystal-clear. Jim had one of those aha moments while working on his

PhD dissertation in the same (or at least nearby) waters that Nansen

had previously studied. All of a sudden, as he looked at the data

that he had studied many times before, he recognized the existence of

a new current that had been overlooked by earlier expeditions (that

is if I remember the story correctly). Jim considers himself

fortunate to have experienced at least one of those bright flashes of

insight at least once during his career, but knowing Jim, I bet it

happens again.

And so it goes. Slowly but surely, cruise by cruise, station by

station, sample by sample, the Arctic Ocean will reveal its secrets

to the oceanographers probing its depths for as Jim Swift

appropriately remarked, "the never-ending quest continues." Or as an

early 19th century explorer once observed: "What a field to feed the

imagination, what a number of ideas rushes in at once, all for the

means to investigate a country so interesting."

No account of my debts would be complete without recognizing the

people that made my parcticipation in this great endeavor possible.

Thank you:

Jim and Team Scripps, all of the graduate students, scientists, and

technicians completing the rest of the science team, Karl and the

Raytheon support group, and Captain Joe and the crew of the R/V

Nathaniel B. Palmer;

The Teachers Experiencing the Arctic program including Arlyn

Bruccoli, Deb Meese, Stephanie Shipp, and April Metz;

The National Science Foundation including Renee Crain;

Merle Bowser of VECO Polar Services and Shelly Easterday of VPR Communications;

Ceth Eslick and my colleagues in the Polson schools as well as the

students, school board members, and administrators of School District

23;

And, a very special thanks to my wife, Sherry Jones, whose

encouragement and love continues to keep this wayward science teacher

on course through the northern mists.

1. John Bengtson's photo of the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer.

2. Jim Swift scrutinizing the data and looking for an "aha" moment.

3. The R/V Palmer plying the Arctic seas.

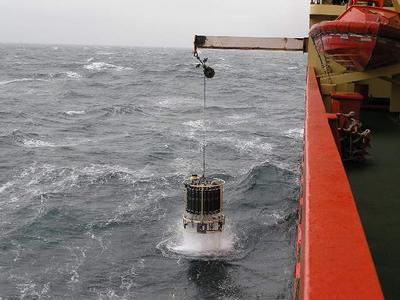

4. Bringing some more data on board.

5. View from the Palmer's bow.

6. What lies below? May the next cruise find out.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|