15 March, 2000

A Night for King Lear and the Fool

74 11 s, 107 38 w

In front of Thwaites Glacier Tongue

Temp 2 C (28 F)

Wind out of east-northeast 45 knots (52 mph) gusting to 55 knots (63 mph)

Barometer 970 mb, dropping

Intermittent heavy snow falling

It is another horizontal snow night. We're in heavy pack, almost

100% coverage. The wind is howling out of the east and northeast, and we

are struggling through a big mass of floe ice that has been pushed over

against the fast ice northwest of Thwaites Glacier tongue. I can tell when

I wake that Captain Joe is at the controls because the diesels are singing

a higher note than usual. He uses the Nathaniel B. Palmer to the fullest of

its capabilities.

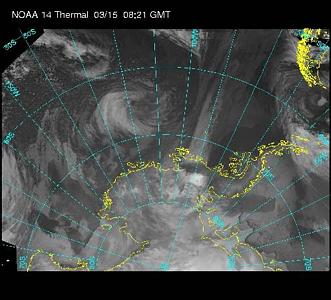

The cause of this ice jam is a storm several hundred kilometers in

diameter centered several hundred kilometers offshore. You can see it on

the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) image with this

journal entry. It certainly looks harmless enough in this "thermal" (does

that mean infrared?) image. Notice that the circulation is clockwise around

the low pressure area at the center, because this is the southern

hemisphere. Also notice part of another storm visible in the Drake Passage,

between the Antarctic Peninsula and the southern tip of South America.

We've been trying to lower the CTD to get data from close to the

glacier tongue, but the fast moving ice threatens the thin cable. One

large block could part the wire, sending an expensive instrument to the

bottom of the Amundsen Sea, never to be seen again. We would very much like

to get a good Kasten core here, also. The Captain has tried several places.

He is trying to open and maintain a hole by use of the ship's engines and

thrusters, but has been unable to maintain a clear space long enough to

lower and retrieve the device safely. Finally he decides to move north and

east somewhat, to escape the worst jammed ice.

Five kilometers northeast things aren't quite as bad, and the CTD

goes down into the cold water. The bridge, the Baltic room and the dry lab

are in constant communication, trying to get the data needed with minimal

risk of loss. At one point a floe four meters across drifts alongside the

ship and catches the cable momentarily. When the cable releases it snaps

back and forth like some huge violin string.

On Sara Searson's computer screen the temperature line shows warmer water

deep underneath us, an extension of the Circumpolar Deep Water. If what Tom

Kellogg thinks is correct, this relatively warm water has a lot to do with

"basal melting", or melting of the bottom of the Thwaites and Pine Island

Glaciers.

After the CTD comes up, it's our turn to try getting a Kasten

core. Out on deck the wind noise, combined with that of the winch

machinery, makes conversation difficult. The snow finds little cracks in

our clothing unless we hide behind something. A moving jumble of ice

surrounds the ship. We lower the corer into the water, and retreat inside.

In this depth, more than one kilometer, it takes over a half-hour for the

corer to get to the bottom and return. I take the opportunity to fiddle a

tune or two, to bring us luck in filling the core box.

When the core comes back, we've got good recovery, the first of

three good cores for the night (and of course it had nothing to do with the

fiddle (probably.))

The weather tonight is a precursor of what is to come in the long

Antarctic winter ahead. In July, when I am mowing hay on long hot Maine

days, this part of the world will be just as dark, and colder and windier

than it is now. The Nathaniel B. Palmer will still be working near

Antarctica. Working in severe conditions isn't done by choice or for the

thrill of it. It's just the way the climate is here, and if you want to do

research, you have to work in a certain amount of poor weather. We

certainly have the best of equipment and the ship to do the job safely and

efficiently.

If you have seen Shakespeare's play King Lear, you may remember

the scene when Lear, abandoned by everyone except his jester, wanders at

night in the storm on the moors. It is that sort of night here tonight.

I got a good look at a large Leopard Seal yesterday. The seal

people are especially anxious to sample Leopards, because they are more

rare than Crabeaters or Weddells, and proportionately less is known about

them. The Nathaniel B. Palmer stopped next to the small floe where the seal

was hauled out.

The famous explorer Shackleton at one point described Leopard

Seals as having "horrible reptilian heads" and I think that's an apt

description. Their heads are more blocky than other seals. Their mouths are

much larger, and turn up in the corners to give a freakish smile effect.

The way they move their heads back and forth resembles a turtle or a snake.

I haven't seen a baby Leopard Seal. They must be cute and appealing to

human eyes, but I would not describe the adults as cute.

Thanks to Lois Breger, a librarian in South Carolina, I have the

definitive answer to the penguin knee question. The answer is yes, penguins

do have knees, and kneecaps also. Lois pointed out that there is a book by

a David Feldman called Do Penguins Have Knees? I'll have to find it when I

return to school.

With yesterday's and today's journal entries I've included photos

taken from one of the Nathaniel B. Palmer's two Zodiac inflatable boats.

Since we were not coring yesterday morning, I had a chance to go out with

the ice people to do their morning satellite pass observations. It was a

cold morning for cruising around in an open boat, but it was nice to see

the ship from a distance. Since we were stopped anyhow, the seal people

took advantage of the chance to get DNA samples from some nearby Crabeater

seals. They came along with us, and we left them on the pack ice, to be

picked up on our return. We continued until we were a kilometer away from

the ship. Steve Ager nosed the boat onto some new ice and stopped the

motor. I collected some sea ice, slush, and seawater samples for oxygen

isotope analysis by Doug Introne, my roommate. While I was doing this, Dr.

Shusun Li and Xiobang Zhou worked on their observations. I haven't yet

found the time to ask them for a full explanation of what they are doing,

but I have it in mind.

The Kasten corer comes up through the ice just north of Thwaites Glacier Tongue. I fiddled it down and fiddled it up, and it brought up over a meter of core.

King Lear's storm. It doesn't look like a whole lot here, just a clockwise swirl of clouds. There is another one on the right, between the Antarctic peninsula and Cape Horn. Thwaites Glacier and Pine Island Bay are at the center of this NOAA image.

High overhead a satellite passes as Xiaobing Zhou (visible) and Shusun Li (under blanket) take optical measurements. Shusun is hiding under the blanket so that he can see the screen of a laptop computer he is using to record data. I still don't know exactly what they are measuring, except that they want to compare their measurements to those of the satellite. The Zodiac can go through young gray ice a couple of inches thick; we're stopped on some now.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|