|

|

13 August, 2001

Fun With Bacteria Monday, 13 August 2001

Hej! Hur star det till? (Hello! How are you?)

Life on Board

Whenever we have a really cold day, on ropes and rough surfaces all over

the ship a special kind of ice forms. Rime ice can take many forms and

shapes, depending on the temperature of the air and the surface it forms

on. The most spectacular form is long spicules of ice crystals. Some of

these form when small drops of water fall onto the surface then freeze on

the outside, forming a small shell of ice with water inside. Pressure

inside this little package builds then bursts open the shell, spitting out

a smaller drop of water that spatters around the outside then freezes. The

drop freezes up again then bursts open again, spitting out an even smaller

drop that also freezes, and so on. This results in a sort of

fireworks-looking rime ice crystal. There is a whole science behind these

crystal formations but regardless of that, the outcome is a beautiful work

of nature's art.

Where Are We Now?

It was a cloudy day with light snow most of the day. Our coordinates at 2

pm were 88o25' North by 1o36' West, so we are still drifting west.

Scientists at Work

Whenever we take a microlayer surface sample, it must be processed for

bacteria. Johan Knulst, from IVL, Aneboda Research Facility in Sweden,

collects these microlayer samples from open water leads that form near the

ship whenever it is not too windy for his little sampler boats (everybody

volunteers to help him because they like to drive these little

radio-controlled boats, especially the guys on board). Surface layer

samples are collected in bottles on the boats, picked up by a

specially-coated rolling drum at the front of the boat. Whenever you see a

smooth smear (a slick) on the surface of a body of water, it is probably

the result of a concentration of organic compounds and microorganisms,

which tend to stick together. You can feel the difference between his

microlayer samples and pure water. The microlayer sample feels more

viscous and oily than water, even though these in the Arctic are

naturally-produced organic compounds. Back in the lab, he splits the

sample into very small 2-mL vials, then adds a specific amount of a basic

protein called leucine to each one. Johan wants to see how active the

bacteria are so the vials go into the freezing incubator for 24 hours,

giving the live bacteria a chance to gobble up this protein snack. What

the bacteria don't know is that this is special leucine that contains

tritium, a low-radiation isotope of hydrogen, which can be later counted by

an instrument called a Liquid Scintillation Counter.

After 24 hours, we bring the vials into the lab and "fix" them (that is a

biologist's way of saying kill them) with another compound called trichloro

acetic acid, or TCA. Then, we put the vials into a centrifuge and spin

them really fast, concentrating the bacteria on one side of the vial.

Next, without disturbing this bacteria "pellet," we suck out the leftover

leucine and seawater using what Johan calls the "slurpee," a suction device

that sounds like that thing the dentist puts in your mouth. Then we wash

and centrifuge and slurpee the bacteria twice more and finally add some

other stuff called a scintillation cocktail (yummy!) that allows the

radioactive isotope to be counted by the instrument. As a matter of fact,

it is 9 pm and yesterday's bacteria are ready to have a ride on the

merry-go-round. Off to the circus I go!

Vi ses! (See you later!)

From Deck 4 on the Icebreaker Oden, drifting west, north of 88,

Dena Rosenberger

Rime ice formations on the ship's anchoring rope

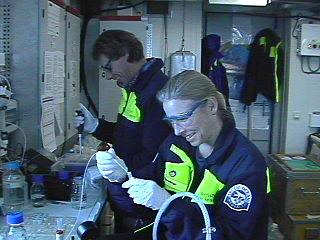

Me and Johan Knulst processing bacteria in the lab. I get to slurpee!

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|