22 October, 1996

One of my responsibilities on Tuesdays is to feed the anemones that we use

in bioassays. Once a week they get one freeze-dried krill. An anemone looks

more like a plant than an animal. It has an array of tentacles that move

above its body like branches on a bush. The tentacles move through the water

column and wrap around objects that touch them. It has a mouth in the center

of the ring of tentacles which it shoves its prey into along with its

capturing tentacles. They look like they are licking their fingers after a

meal.

The anemones, along with a number of other organisms, are kept in an

aquarium building near the ice edge. Typically Jim, Pat, or scientist from

other groups conduct experiments with the animals that are housed there. I

saw several rather strange creatures that I didn't recognize. One looked

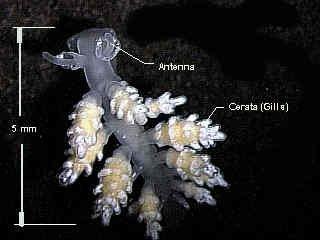

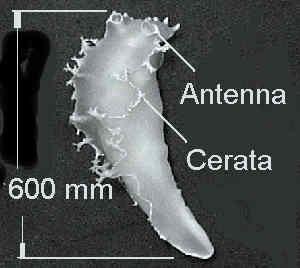

like a white slug. I asked Pat about it and why it had been collected. I

also asked him if he would write about his experiment. He decided we should

include some pictures and identify the body parts of the organism he was

studying. Getting the pictures that I've included took me the rest of the

evening. This is great for me, every day is a new learning experience.

Pat Bryan's work with Nudibranchs

"I am studying both juvenile and adult nudibranchs or shell-less snails

called Tritoniella belli. These are organisms that obtain chemical defenses

through their diet. The juvenile shown is about 5 millimeters long and the

majority of its body mass is covered with cerata or gills. The adult stage

is also shown. A juvenile is defined as the developmental stage of an

organism that follows larval settlement or hatching from an egg, yet

proceeds adulthood. Adulthood is defined by reproductive maturity. Juveniles

often occupy distinctly different ecological niches than adults of the same

species. They often eat different foods, live in different microhabitats,

and have different predators than adults. Yet because of the small size and

often-cryptic (hidden) behavior of most juvenile marine organisms, very

little is known about them.

In the Antarctic, performing research in the field is extremely difficult,

especially when you are diving to a depth of 100 feet in water that is -1.8

C. Fortunately, I managed to find juveniles of the Antarctic nudibranch

Tritoniella belli hiding among the branches of an Antarctic hydroid.

Nudibranch's often incorporate chemical or structural defenses from their

diet into their tissues. However, the mechanism of "borrowing" defenses from

other organisms is poorly understood. By studying juvenile nudibranchs we

may be able to determine how these types of mechanisms develop and are used

by the adults.

My specific interests concern the development of chemical defense

strategies in marine invertebrates. I want to find out if organisms that

possess some type of a defense as an adult possessed this same defense all

their life or if the defense is specific to the adult stage. Moreover, if

juveniles do have different predators and diets than adults of the same

species, they may utilize different defensive strategies than the adults.

Hopefully, I will be able to determine if juvenile Tritoniella belli can

defend themselves from predation and if this defense differs from the

defense strategy used by adults. If the defenses are different, I would like

to find out how and when the change takes place. With the help of everyone

in S-022, we will find out all about this nudibranch during this season on

the ice."

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|