27 July, 2002

Due to the great depth (2000 meters) at this station,

we only did the Haps core sampling for the mud at the

bottom. The five van Veen grabs would take up too

much ďwire timeĒ (the time it takes to send the

equipment down and back). The multi-Haps core sampler

should pull up four cores at a time and, by sending it

down twice, Jackie will have more than enough samples.

However, it is not unusual to run into problems,

especially at these depths, both due to equipment and

changing drift conditions. Today we had to send the

corer down three times in order to get the samples we

needed. Thanks to Steve Roberts, the JOSS (Joint

Office of Science Support) data management person on

board, I have a record of the sampling process. Be

sure to check it out in the series of pictures below.

Keep in mind as you look at the pictures that Jackie

Grebmeierís interest is the benthic organisms. Itís

important to understand what lives at the bottom and

the characteristics of their environment (the

sediments) in order to see what part they play in the

overall scheme of carbon cycling. When the cores come

up, sub samples of the sediments from one of them are

taken for a variety of tests. A chlorophyll test

gives an indication of the phytoplankton present in

the sediment. Remember that phyto means plant and

phytoplankton contain chlorophyll, a green pigment

found in all plants. Another sample is collected for

HPLC analysis. This is high performance liquid

chromatography, a fancy name for a process that

separates out the phytoplankton by the pigments

(colors) they contain. Another sub sample yields TOC

(total organic carbon) and TON (total organic

nitrogen). The results can provide an indication of

the source of the organic material in the mud, a ratio

of marine (salt water) to terrestrial (terra = land)

organisms. Carbon-13, an isotope of carbon, will be

analyzed from the same sub-sample and will provide

similar information. Lastly, we preserve the samples

for analysis for a series of radio-isotopes such as

beryllium-7, lead- 210, cesium-137, plutonium, and

radium. These are called tracers because they tell us

what forms of carbon and how much arrives at the

sediment surface from overlying water column

processes.

Once all the cores are on deck and the sub-samples are

removed, Jackie chooses two cores for her 12-24 hour

respiration experiments. (Check out the journal

photos for July 22.) When she is finishes with

those, they are sieved to remove all mud and to

preserve the organisms left behind. We then take one

of the other cores collected to cut into sections to

be canned and brought back to the University of

Tennessee for further analysis. Thatís the time when

we get to come inside and actually work with the mud.

When itís not full of byssal threads from mussels in

the core, itís an easy job. We take off one

centimeter (a little less than Ĺ inch) slices at a

time for the first four sections. After that we

remove two centimeter slices until the core is

finished. Because we are near the end of the sampling

at each station, we are often working into the early

morning hours or even through the night. In case you

think that is difficult, check out the last picture to

see what our surroundings look like while we are on

deck!

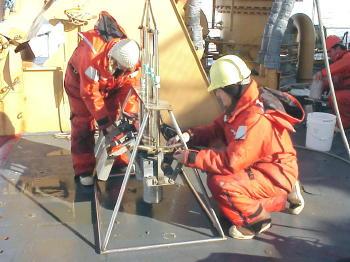

Jackie Grebmeier designed this multi-Haps core. The original design only takes one core at a time. This one takes four. Jackie is the one at the end with the white hat.

Everything must be checked before the Haps goes into the water. Once it reaches the bottom, the tension on the wire releases and the cores drop into the sediment.

There is always an MST (marine science technician) on deck to direct whatever sampling operation is going on. He or she works with another MST who controls the operation of the winch. Together they make certain that the equipment is deployed correctly and safely.

While we are waited for the Haps core to return to the surface I sieved the core from Jackie's respiration experiments. At this depth (2000 meters) there are very few organisms.

It takes at least one and a half hours for the Haps core to get to the bottom and back when it is this deep. Sometimes, when standing on the back of the ship, I am reminded that little separates me from water that is 2000 meters deep!

Lee Cooper, co-chief scientist on board, removes one of the core samples after the Haps comes back on deck. Some of the analysis is his work.

Once we select one core for sectioning, we start at the top with one centimeter slices. This looks like a two centimeter slice that Jim Bartlett (science technician for Lee Coper and Jackie Grebmeier)and I are getting from further down in the core.

As we remove each layer of mud, we collect a sample into carefully labeled cans which will be taken back to the University of Tennessee where the mud will be analyzed.

Working into the early morning hours has its advantages. Look at the view we get from the back deck!

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|