19 October, 2004

Diving at last!

Today was a great day because I was able to go out for the first time and see the divers at work.

First, I went with Andrew down to the dive hut at the jetty to retrieve the current meter that had been hanging in the water recording data all night. Next, we all had a meeting with "Mac Ops," short for McMurdo Operations, who are in charge of communications around the station. A large part of what they deal with is radio communications - the main way that researchers in the field keep in touch with the station. Before leaving the station, even for a short time, everyone is required to radio in to Mac Ops and tell them:

Number of the vehicle

Number of people in the group

Destination

Event number (in our case, the science event number)

Driver name

Time of return (on a 24-hour clock, so 5:00 pm would be 1700)

Name and number of point of contact - person to contact if necessary.

Mac Ops is then responsible for starting the process to find people if they don't come back by the designated time.

Next week, we will be going to Cape Chocolate, across the sound, and will be at field camp for three days. We will get two different types of radio - VHF (very high frequency) and HF (high frequency) to take with us to check in each day.

Next, it was time to go diving! First the Pisten Bully was loaded with the tanks, dive gear, cameras, food, kitchen equipment, and emergency equipment needed for today's dive. I picked up the Mattrack from the parking lot, doing the morning check for fuel, fluid levels, and the tracks. I also got to drive it - my first time driving on the ice road - out to Cinder Cones, the dive site. Approaching the dive site, there were a lot of cracks in the ice, but we successfully made it over all of them.

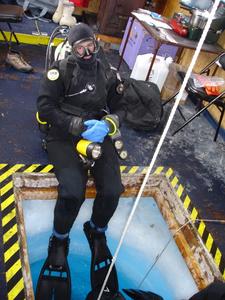

The dive hut, which had been towed out on the ice over the dive hole, was quite warm when we arrived because Stacy had lit the "Preway" stove the day before. The divers started getting their gear ready. First they put on a fleecy warm layer, then their dry suits. Over that went their weight belts and dive tanks. The suit includes a tight hood and when the gloves are wrestled onto the diver, the whole thing makes a seal so that no water can get in. Finally, the divers put their fins on, put regulators in their mouths, and slid from the floor of the dive hut down into the hole.

Today their mission was to take pictures, collect cores from the bottom, count siphons of the clam Laturnula, and check on experimental areas that had been set up two years ago. First Stacy and Bob went in, then Jennifer and Andrew. After they went down, both Eskil, the dive tender, and I looked longingly into the dive hole and wished we could go down there too. The ice was about 12 feet thick, and almost glowed blue with light in the hole. The water was so clear that we could see the divers and some equipment near the bottom in over 50 feet of water. Everyone came up excited about the things they had seen: a nudibranch (sea slug) the size of a football, sea stars, sea spiders, various types of sponges. We hauled the core samples up in buckets and put them in a cooler. (See below for pictures of the cores.)

On the way back, Stacy and Andrew flagged a safe route around some of the rather gnarly cracks in the sea ice between the ice road and the dive hut. That way, it will easier to get there for future dives.

Back at the lab, the core samples had to be sieved - passed through a fine mesh - to sort out benthic animals - specifically the infauna (animals that live IN the sediment at the bottom). The sorted samples were then put in bottles, and will be preserved and shipped back to California to be analyzed. This process takes a lot of care and patience. The goal is that every organism in the core, no matter how tiny, makes it into that sample bottle. This includes making sure to get all the sediment from the core container into the sieve, and using forceps to pick out every animal that gets stuck to the mesh of the sieve. It's meticulous work, but really interesting and fun. In the cores I sieved, I found sea urchins, sea stars, anemones, isopods and other crustaceans, small mollusks called Yoldia, and various types of worms. Some of the cores even had a sluggish fish sitting on top. Once the sample is back in the lab in California, all the animals in each sample bottle will be iden

tified and counted. The scientists will then be able to compare one research site to another in terms of - among other things - diversity (how many different species there are) and abundance (how many there are of each species). The researchers will also need to analyze the pictures taken.

Andrew was just saying he feels funny e-mailing home describing his "work" day as diving, drinking cocoa and eating lots of chocolate, and working in the lab. How would you like to have that as your job?

1. Andrew rinses off the current meter after it has been in the water overnight.

2. In the Mattrack (a pickup truck with tracks instead of wheels), we follow the Pisten Bully to the dive site.

9. Although the core samples are taken to find the infauna (animals that live IN the sediment), it's always interesting to see other animals, like this Trematomus bernacchii, or Emerald Notothen, that sit on the bottom and sometimes end up in the cores.

4. Looking into the dive hole. The ice below is about 8 feet thick. Before diving, loose ice that has formed on the surface of the water overnight must be removed with a net and dumped outside.

5. Jennifer gets ready to dive. Note the camp stove in the background, ready to heat water for hot drinks after diving.

6. Flagging a safe driving path around the cracks in the ice. Andrew has the drill to make holes for the flag poles.

7. Sieving the cores. The cores are collected at the dive site by pushing the clear tube into the sediment at the bottom and capping it to enclose the sample.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|