20 June, 2000

The All-nighter: A Slow Decent into Mud

I don't know if it was the excitement from seeing a mother polar bear and

her two cubs at 8:30 last night, but I was able to stay alert until 02:00

A.M. I took the first watch of the all night bathymetric watch, from 10:00

P.M. until 2:00 A.M. You might be asking, "What is a bathymetric watch?"

Drs. Larry Lawver and Lisa Clough, along with Jay and myself took turns

watching the Seabeam and Knudsen data which gave a detailed mapping of the

ocean floor.

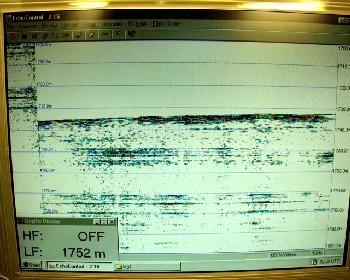

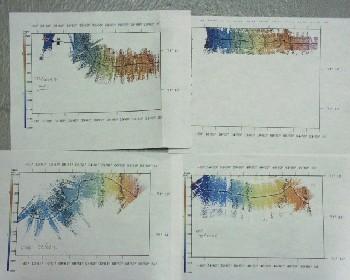

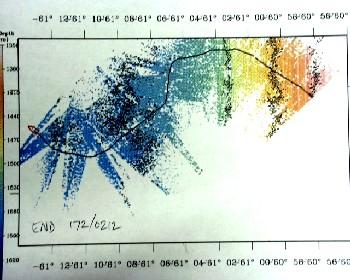

The sonar equipment mapped the topography of the ocean floor were we

sailing above. The Seabeam system profiles the topography not only below

the ship, but out away from the ship at a 60 degree angle, helping to

profile a larger area than the normal sonar imaging. The Knudson sonar gave

us two readings to interpret, a bottom profile and a subbottom profile. The

bottom profile gives an image of the first layer of sediment on the ocean

floor that the sonar detects. The subbottom profile indicates whether or

not there is a layer of sediment above a bedrock base. Some of the sonar

signal penetrates the surface of the sediment and continues down to a lower

level, until it is also reflected back to the surface. If there is another

layer, its echo pattern forms parallel dark bands on the image. The top

band represents the top layer of sediment and the bottom band represents the

top of the rock or more compacted sediment layer below.

We were sailing to look for a desirable location to complete a rock

dredge. The sort of terrain we were looking for was an area of the ocean

floor with a steep drop-off, much like an underwater cliff. We were also

looking for an area that did not have a layer of sediment; we wanted a rock

outcropping that we could get a dredge bucket hung up on. The plan was to

get the dredge bucket hung up to the point that the tension in the wire was

near its maximum. Either the weak link in the chains that hold the bucket,

or the rock outcropping would give way. Of course, we are wanting the rock

to give way so that we will have some rock specimens to examine.

Just after 7 P.M. we were sailing at 59 degrees 30 minutes North Latitude,

71 degrees 06 minutes West Longitude. By early Tuesday morning we had

sailed to 61 degrees 13 minutes North Latitude, 71 degrees 16 minutes West

Longitude with no luck in finding a suitable dredging location. We were

beginning to realize that we were not going to find that ideal location.

All we could find in the nine hours spent watching the sonar equipment was a

steadily decreasing slope. We initially started with a depth of 580 meters

and ended up at a depth of 1770 meters. This was about the time that I went

to bed. But before I went to bed, plans were being made to stop the ship to

determine the rate at which the ice we were in was drifting. To determine

the drift from winds and/or current was important for the over-the-side

coring operation that would begin around nine to ten in the morning. After

determining the drift, the ship was then going to sail until the bottom

topography leveled out and showed a deep layer of sediment. The deep layer

of sediment will be necessary for getting a 30-meter core during the coring

operations today.

As I try to instill in my students back home, "Science isn't always

pretty." Lab work in real life applications doesn't take fifty minutes,

like typical classroom experimentation. Many scientists spend weeks, even

decades studying the area of science they are most interested in. And even

though you might spend an enormous amount of time and energy completing a

specific task, it certainly does not guarantee that you are going to get the

results you expected and hoped for. As the old saying goes, "If at first

you don't succeed, try, try again." Yes kids, that means we are going to

have to do it all again! "Oh, man."

Photo by: Lt. MacDonald

Drs. Lisa Clough and Larry Lawver standing watch. Photo by: Jerry Oldam

A Knudsen image. Note the dark parallel bands, indicating layers of sediment.

Mother polar bear feeding her two cubs. Photo by: Lt. MacDonald

Photo by: Lt. MacDonald

Four Seabeam images, follow them along from left to right, top to bottom.

One Seabeam image showing the underlying depth of the ocean floor.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|