|

|

12 December, 2001

I stopped by the weather station at 8 a.m. to get an update on the weather. Although, it hadn't been formally announced, I was told that the weather could possibly detain me for a couple of days. While at the weather station, I met the crew on duty at that time. Weathermen Chester Clogston and Jim Fodge gave me a tour of the weather station. They are both retired from the navy, and they now work for Naval Space and Warfare Command. Although this is Jim's first year in Antarctica, he brings 22 years of weather experience with him. Chester majored in meteorology and oceanography in college. He has an engineering and electronics background. The navy provided weather services in McMurdo in the 1950's, but civilians began to run the weather station in 1977. This weather station is on a 24 hour a day/ 7 day a week schedule with the crew working 8 to 12 hour shifts.

"Spike" is helping one of the forecasters track the weather. In 1955, observers made hourly observations and collected data in town, at the runways, and in all field camps. This information was typed on spreadsheets. Today, meteorologists rely almost exclusively on computers to look at numerical models based on global (the world/big picture) and mesoscale (information from a specific area, such as Antarctica). Forecasters brief pilots from data collected from satellite pictures, numerical models, and automatic weather stations. These automatic stations transmit one-minute readings every ten minutes. A balloon is sent up twice a day to make surface observations, which give a vertical profile (skew-T) of the atmosphere. Observers are still used in town and on active runways to take hourly observations. They check cloud cover, cloud type, temperature, and pressure. Forecasters make decisions about what is going to happen in order to make forecasts for ships, aircraft, and all Antarctic operations. In today's world, information is transmitted out globally, and weather trends are available to the rest of the world. My students are making daily observations and collecting data on cloud cover, cloud type, temperature, and precipitation at the atmosphere site at our school. They use a wonderful web site (www.antarcticconnection.com) to compare and chart the maximum temperature at West Elementary to McMurdo Station and the South Pole.

Weather instruments and radar on top of the building at the weather station help track the weather.

This photo was taken several days later near the door of the weather station. The snowdrift towered over my head. Three lows forming a circular pattern around the McMurdo Station and the moisture from the sea made the conditions that brought snow to McMurdo. This was the worst summer blizzard in nine years. (See journal entry, December 15th for more information on the blizzard.)

MacOps (McMurdo Operations) is the safety net for all that come to the McMurdo area. Tina Green, one of the operators at MacOps works a 12-hour shift (3-weeks/night schedule and 3 weeks/days). This is her second season in Antarctica. She had three days training in Christchurch, then hands-on training in McMurdo. Our field camp relied on MacOps when we made "com checks" when we left camp, made dives, and basically woke up each morning. Every camp must call in at a scheduled time. If a call isn't made within an hour of the scheduled time, the operator will notify SAR (Search and Rescue). Anyone leaving McMurdo must make give information and departure and return times. All schedules and regulations are adhered to because safety is of utmost concern in a land where the weather can change without a second's notice.

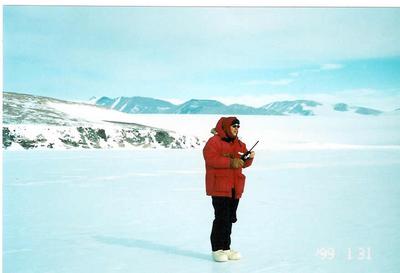

Organization and care is taken by the operators to track everyone going in and out of McMurdo. A VHF, very high frequency radio, is used whenever someone leaves the area. We relied on them constantly at our field camp. HF, High Frequency, Mash type radios were also used from remote field camps to reach other areas or Mac Ops. When the helicopter let us out on the sea ice miles away from our field camp and McMurdo, it was very comforting to know that we were not alone. McMurdo knew our location and expected time for return. Due to rapidly changing Antarctic weather, we (Dr.Bowser, Dr. Pollock pictured above) disembarked from the helicopter with equipment, supplies, and survival gear. Precautions are a way of life in Antarctica.

When we were dropped off on the sea ice at Gneiss Point, the first thing Dr. Bowser did was to establish radio contact with MacOps.

This communication board at MacOps is connected to all field camps to ensure safety. The computer, along with the radios, is used to keep track of all field camps, including field camps in the remote field.

When I went to dinner later in the day, I met with someone who told me that I needed to see the bowling alley before I left McMurdo. Although, I didn't bowl, I wanted to see how this "manual" bowling works.

I met Dennis, someone who works on engines at the VMF building (See journal entry, December 14th) setting the pins at the bowling alley in McMurdo. He instructed me on how to manually set the pins and return the bowling ball back down the chute.

I set the pins and manually lowered them back to the floor. I really enjoyed the behind-the-scene visit to the bowling alley.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|