25 February, 2000

Back in Open Water

February 25, 2000 11:40 PM local (same as Alaska) time

74 30 s 133 49 w

"On Station" 300m (980 feet) off the Getz Ice Shelf, in 1002 m (3284 feet)

depth

-5 C (23 F)

36 km/hr (22 mph) wind out of the west.

Clear sky, half moon shining.

3-4 foot black waves, occasionally breaking crests.

Barometric pressure bottomed out two hours ago and is rising.

As I write this we are stationed above a huge trough in the sea

bottom of the Antarctic continental shelf. Past glaciers, including the

one which peaked 15,000 years ago, gouged these big channels out of the

bedrock (The Bay of Fundy is another glacial trough). Knowing where, how

big, and how many of them there are will help predict what's going to

happen to the ice sheet in the years to come. So what? What does this big

empty refrigerator at the bottom of the world have to do with people in

Kenya, Iowa, Hong Kong, or Peru? A lot, in terms of future climate and sea

level. In the largest sense, that is why this ship full of scientists is

down here.

I've started writing knowing that I'm going to get interrupted in

the middle to assist in taking a core of the sediment at the bottom of the

trough. Dr. Tom Kellogg wants this core because he hopes it will tell him

how long ago it was that the ice thinned and the watered moved in

underneath the ice edge here. When he gets samples back to the University

of Maine, he'll carbon date them. Hopefully, he will be able to date the

pull back of the ice, and fit another piece into the climate crossword

puzzle. I'll get you a picture of the long, thin stainless steel box we

lower down to get the sample. It's called a Kasten corer.

I've had a busy last twelve hours. Here's an account of what has

happened today.

At 7 AM we nosed into an immense ice floe, several miles across, and I got

a chance to go out with "the ice people," that is Dr. Shusun Li and his

group. The day was clear, bright and dry, but I dressed up in my all my

cold weather gear anyhow. A nice late summer morning here is like a nice

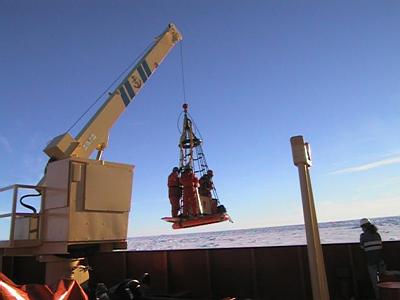

midwinter morning in Maine. We were lowered down to the ice floe surface

the same way we boarded the ship, using the forward deck crane and a netted

ring to stand on. When I got down on the floe, it was like being out in an

endless Kansas farm field in midwinter, except for the huge ship beside us

("This isn't Kansas, Toto!). We set up various instruments and dug two pits

in the snow to take samples and measure temperatures. Our trip out on the

ice was timed to happen when a satellite was overhead, so our measurements

could be compared to those from the satellite. I haven't had a lot of time

to talk with these people and find out exactly what they are doing, but I

know it has something to do with how heat flows in and out of ice covered

surfaces. After I ask them a lot of questions, I will show you some more

pictures and try to explain what I know. You could probably find out more

now by looking at the web site of another TEA teacher, Marjorie Porter. She

has been able to work with these same scientists several times before.

We came back aboard for breakfast, leaving some of the instruments out on

the ice to collect data automatically. After breakfast, the "ice people"

went back to retrieve their equipment. The 'core people" took a piston

core. The "core people" are Tom Kellogg's group, the group to which I

belong. (We also have "the seal people" and the people who take CTDs, who

are just called Stan Jacob's group.) We took a core not because we had a

special reason to, but because we had the time and wanted to use the ship

and our opportunity as efficiently as we could.

About noon we were done with the piston core. I had been up since seven

o'clock the night before, so I was pretty exhausted. I took a shower and

climbed up into my bunk.

At 9 PM I woke up. I could tell we were doing a CTD because I could hear

the whine of the winch. I've gotten so I can tell the sound of the

different equipment on board. I heard the thrusters working also. They are

needed to keep the ship in position while the CTD is in the water.

I got quite a surprise when I looked out my porthole, and saw miles of

open water and an ice shelf edge extending from horizon to horizon south of

the ship. While I was sleeping we'd gotten out of the pack ice and into a

large area of open water near the Getz Ice Shelf. This is the same area

we'd seen in the satellite images. I felt a sense of freedom, being out of

the pack ice. I don't know why that should be, because I'm more confined to

the ship than before. Maybe it was just that the ship could move easily and

relatively quietly in the open water.

A few huge tabular bergs were visible, five or six miles away. Since we

were not over the trough at the time, I suspect these were probably

grounded. I tried to imagine what it would be like to be stranded on one of

them in the dark, looking at the ship from that distance. It's not a very

pleasant thought!

(Later) I've just been out on the aft deck for a couple of hours, helping

get cores. Things don't always work perfectly. We spent most of an hour

lowering the Kasten corer to the bottom, then hauling it back up. For our

troubles, we ended up with about 30 cm of mud in the bottom of the two

meter core box! My guess is that the bottom sediment is so hard that the

corer hit the bottom and fell over on its side.

This is a critical place to get a core, so we decided to take a piston core

instead. Another hour or so, and our efforts were rewarded. We retrieved a

nice full core barrel. As we cleaned, labeled and stored the core, the ship

moved on to the next station.

While I'm writing this, the sun is rising. At its low angle, it lights up

the Getz ice shelf, the blue black water, and an occasional berg or bit of

floating ice. Twenty miles to the east, where we will pass later today, I

can see exposed rock, a north facing mountainside. It is the first terrain

besides ice, water and sky we've seen in days.

Question for today: We are near the shore, in open water. According to the

satellite pictures, there is a lot of open water within a few miles of the

ice shelves and shores, but further out there is a wide band of pack ice.

What causes the open water near the shore?

Here's the Nathaniel B. Palmer in the middle of a Kansas corn field. The ship and the corn field are floating in about 1100 feet of water.

It's a pleasant ride from the bow deck to the ice, but hold on tight!

This is the Kasten corer, after our first try at getting a core in the trough. You can see there's not a lot of mud in the long, square coring box. My fingers are cold. The second time we were successful!

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|