17 November, 1999

As I crouch inside this cavern with its beautiful, diffuse blue light and

delicate ice crystals dangling from the ceiling, I can't help but think back

on the course of events that brought me to this place. Two years ago making

application for the TEA program; the waiting and anticipation; getting word

from the head of the NSF Division of Elementary, Secondary, and Informal

Science Education (ESIE) Wayne Sukow that I had been selected. The planning,

the school visits, the apprehension. Meeting with John Wrenn and the

training at LSU. And, then the travel. Appleton to Los Angeles, then to New

Zealand; the C-141 flight to McMurdo; then an hour helo flight to Cape

Roberts. Finally, a bumpy, hour-long traverse across the frozen Ross Sea in

a Haggland has brought me to this place. I find myself inside an ice cave at

the front of the Wilson Piedmont Glacier on the coast of the Antarctic

Continent. My companion, Wojciech, and I have made our way into a small ice

cave. The cave has no footprints in it. We may be the first persons to enter

this parcticular cave. It is quite exhilarating.

Ice caves are formed by melt-water inside of a glacier as it runs toward the

sea. The running water carves a tunnel in the ice. The tunnel may get so big

that it becomes a cave. The largest of the ones we explored was about 20

feet across and 15 feet high and extending back into the glacier about 50

feet or so. We also crawled into some very small, delicate caves as well.

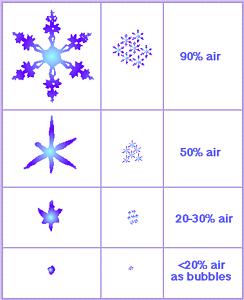

The light inside the cave comes from the sun passing through the blue

glacial ice. In ice caves the ice is so compacted that it looks blue. The

color is due to how the light interacts with the frozen water. Loose and

compacted snow has a lot of air bubbles in it. As light passes through it,

it appears white because of the presence of the air bubbles. (See diagram

below) A blue tone indicates that the pressure from overlying ice and snow

essentially has eliminated the air bubbles in the ice. The less air bubbles

the bluer the light will appear as it passes through.

Inside the surfaces of the ice caves there is a coating of very

delicate ice crystals. Some of the individual crystal are quite large (.5cm

or larger). However, if you touch them or accidentally bump the side of the

cave, the crystals disintegrate into a shower of fine snow. It is just a

marvelous sight. These ice crystals forming a white deposit, called hoar,

results from moisture recrystalizing from the air inside the cave.

Ice caves can be dangerous. Glaciers are dynamic places. The ice is under

stress and is moving. There is often an overhang of snow at the entrance to

the caves. We took precautions when entering the caves. We never went alone

and there was always someone around to help in case of a problem. I am glad

I had the opportunity to explore such a magical place. It was truly an

awesome experience.

Here is an update on the Cape Roberts Project. The drillers have reached

almost 900 meters. The scientists have been confronted with a big surprise.

They have drilled into rock that they did not expect to find. This is true

exploration. The geologists of the CRP hypothesized as to what they would

find when they drilled into the seabed of the Ross Sea. They thought they

would find rocks of the Oligocene epoch then below that rocks of the Eocene

epoch. Instead, they have drilled into rock that is found in outcrop in the

TransAntarctic Mountains that is much older then the rock they expected to

find, perhaps Devonian in age. They are not sure why this rock is where it

is. Many ideas have been discussed, but it is clear to me that in the

process of unraveling this mystery, the geologists will learn a lot that

they don't now know about the geologic history of the Transantarctic

Mountains and the continent of Antarctica. This is science at work. I will

keep you updated as the story unfolds.

Today's featured CRP Team members are a group of Italian petrologists. They

are Franco Talarico and Soyna Sandroni both from the Earth Science

Department at Siena University and Massimo Pompilio from the Institute of

Volcanology in Catania, Italy. This group of geologists is studying the rock

fragments, or clasts, that are imbedded in the sedimentary rocks in the

core. By determining the age and type of clasts, they can make a

determination about the nature of the area surround the place where the

rocks were deposited. So far, they have examined over 20,000 clasts!

As ice is recrystalized under pressure, it forms with less and less air bubbles. Glacial ice has little air in it.

The Haggland vehicle that took me to the ice caves in the Wilson Piedmont Glacier.

Outside the entrance to an ice cave.

The blue color of the light filtered through the glacial ice.

The view through the entrance.

This was truly a thrill of a lifetime.

From left to right: Franco Talarico, Sonya Sandroni and Massimo Pompilio. 20,000 plus clasts is quite an accomplishment.

Contact the TEA in the field at

.

If you cannot connect through your browser, copy the

TEA's e-mail address in the "To:" line of

your favorite e-mail package.

|